What is the best way to address climate change? If too much carbon is released in the air, how can emissions be reduced? By regulating corporations or by imposing costs on consumers in the form of a carbon tax?

Moreover, even if a solution is found, not all nations, and not all people within nations, will agree on how to tackle the problem. In the words of Professor Barry Rabe, author of Can We Price Carbon? “Compelling ideas from economics do not necessarily suspend the laws of politics.”

On May 4, 2023, Jessica Green, professor of political science at University of Toronto, reminded an audience of Rabe’s sage observation when she delivered a webinar on the effectiveness of carbon pricing. This was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics. She reported results from her 2021 paper published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, titled “Does carbon pricing reduce emissions? A review of ex-post analyses.”

Green’s research examines many aspects of “the politics of carbon markets,” such as the role of firms and governance, and especially “non-state actors.”

“Carbon pricing is a hard sell politically,” she said, especially in this time of rising prices. “Costs are visible and upfront, while benefits are in the distant future—a recipe for political failure.”

“Can revenue recycling help dampen opposition?” she asked. Revenue recycling refers to when income generated from carbon taxation is reserved and returned to society. “It can help,” she noted, “but not always.”

Another drawback to carbon pricing, she said, is that “it changes with the political winds.”

Her research on the effectiveness of carbon pricing was a meta-analysis, namely, a systematic review of research already published. All papers she selected for inclusion in her paper had rigorous “ex-post evaluation” and excluded models. Ex-post evaluations are used throughout the European Commission (EC, here used interchangeably with EU) to assess whether a specific intervention was justified and whether it worked (or is working) as expected in achieving its objectives.

An ex-post evaluation is different from a final evaluation. According to the EC/EU website, “Unlike final project evaluations, which are completed at the time of a project’s conclusion to assess whether or not it has achieved its intended goals, an ex-post evaluation is conducted in the years after a project’s official end date – maybe one, three, or five years after the fact.”

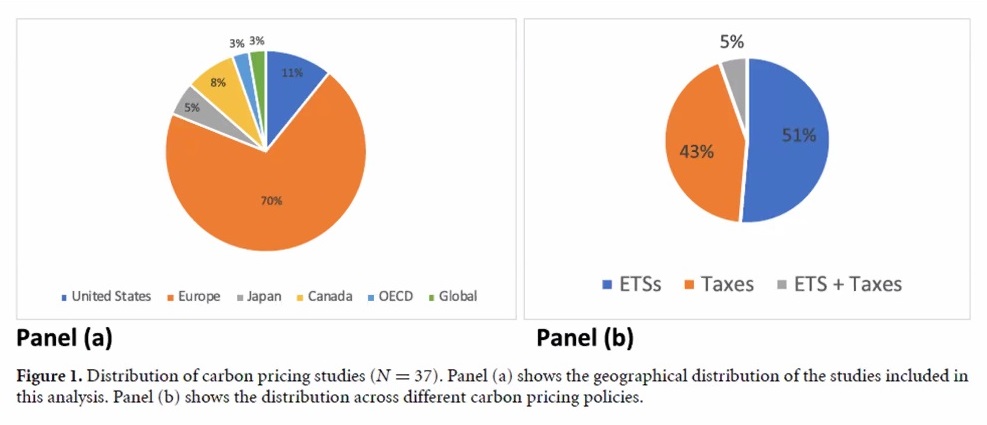

“I found only 37 ex-post studies,” Green said. Most were from European sources; only 11 percent were from U.S. sources. (See chart below.) Carbon pricing was done through emissions trading schemes (ETS), taxes, and a mixture of the two.

“A key finding is that carbon taxes tend to produce more reductions than ETS,” Green said. “The overall effect on mitigation is small: 0 to 2 percent, but there is sectoral variation.”

The drivers of the reductions observed were: fuel switching, enhanced efficiency, and reduced consumption of fuels. There was limited impact from the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). This is a cap-and-trade arrangement where a limit is placed on the right to emit specified pollutants over an area, and within that area, companies can trade emission rights. It covers around 45 percent of greenhouse gas emissions within the EU.

“The EU-ETS is the most likely case,” she said, “because they have a high political will. Yet we’re not seeing huge reductions.” She noted two studies that showed reductions of 4 to 10 percent.

Another problem with getting political buy-in, Green argued, is that “offset markets have serious integrity issues.”

“Offsets quantify and sell the hypothesized absence of emissions,” she noted, and thus, “accounting challenges make it prone to gaming [the system]—especially leakage and inflated baselines.” In economics, leakage refers to a diversion of funds from some iterative process.

“All the political incentives load for poor quality,” Green said. “The incentives favour quantity over quality… everyone wants cheap offsets.”

“Offset problems are even worse in the voluntary market,” she said, citing an analysis reported in the Guardian that revealed more than 90 percent of rainforest carbon offsets by the biggest certifier are worthless.”

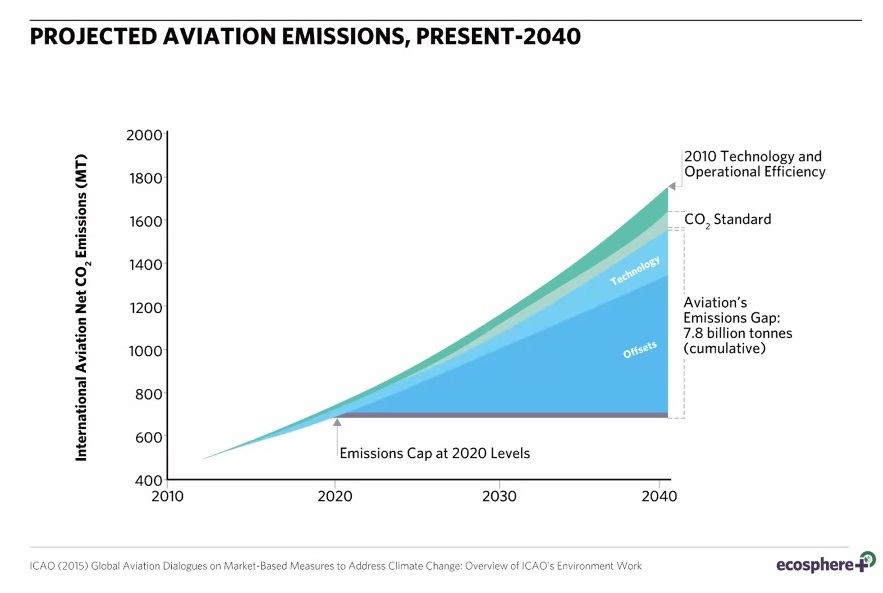

CORSIA

She singled out the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) for special mention. “This voluntary market agreement has a huge reliance on offsets. They are now accepted as ‘compliance grade’ offsets.”

Mandatory from 2027, CORSIA aims to cap international aviation emissions at 2020 levels. Such emissions contribute about 2.5 percent to global emissions, and are not regulated by the Paris Agreement but the industry realizes it needs to do its part.

Mixed signals

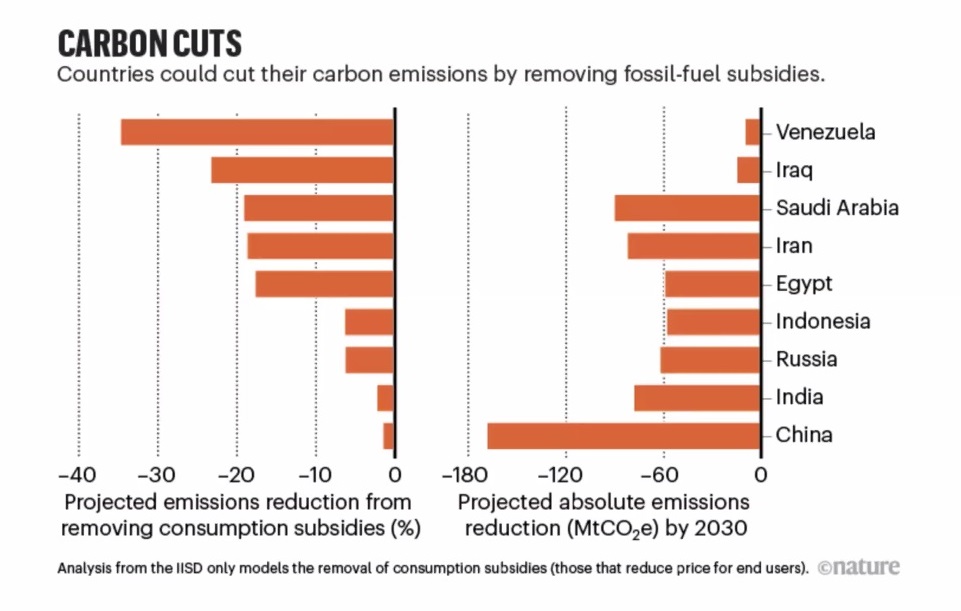

A big problem with carbon pricing lies in the mixed market signals. Fluctuating fossil-fuel subsidies are influenced by the price of oil and the strength of political lobbies. “Countries could cut their carbon emissions by removing fossil-fuel subsidies,” she noted. Reductions can be measured in percentage or absolute terms. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) monitors such data.

She showed a chart, based on the UNEP Gap Report of 2021, that compared emissions reductions from two sources: (1) removing consumption subsidies and (2) absolute emissions reductions, divided by country. Venezuela offers a large subsidy, percentagewise (35 percent), but the absolute emissions reduced are in fact very small. China offers a small subsidy (less than 5 percent), but the absolute emissions would be the largest of all.

“Putting the pieces together, we are expending a lot of human, material, and political resources for a policy that has a limited effect on emissions,” she said. “The ratio of costs to benefits is high.”

Jessica Green posed a series of questions:

- Do we really need the tool of carbon pricing?

- Is it the best use of finite political resources?

- What do we do instead?

Carrots, then sticks

She recommended an approach she called “carrots, then sticks.” The sequence is crucial. “First, green industrial policy is used to provide benefits and build political coalitions. Then we bring in carbon pricing.”

Also, she emphasized we should follow the money. “Focus on regulating dollars rather than tons.” She noted, “at the global level this means shifting the focus from the UNFCCC to trade, investment , and tax institutions.” (The UNFCCC refers to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.)

Her presentation was followed by a lively Q & A.♠️

The charts are from Jessica Green’s presentation. Permission pending.

The carrot-stick visual is from the Media Portal at University of Vienna.

The carbon cuts figure is based on an article in the journal Nature.

Click here to find out about the FRBSF Climate Seminar Series.