“Be careful what you wish for,” the adage goes, “it might come true.” After a year of an ever-broadening pandemic, vaccines have arrived, and thus begins a new round of planning and negotiating.

As the first covid-19 vaccines are rolled out across the world, the magazine the Economist assembled a panel on January 14, 2021, to reflect on the challenges. An audience of thousands tuned in as three seasoned journalists discussed global issues related to vaccine development, the risks of misinformation, and the expected impact of an uneven distribution process of vaccines. The panel moderator was Helen Joyce, executive editor for events at The Economist.

“People should be excited we have vaccines,” said Natasha Loder, health policy editor at The Economist. “This will prevent people from dying from it or catching it” and suffering health consequences. “Vaccine development has helped our pandemic preparedness” for future pandemics, she said. On a side note, Loder said she had lost an aunt to Covid-19 “so it’s become personal.”

John McDermott, The Economist‘s Africa correspondent, based in Johannesburg, painted a vivid picture of the biggest hospital in Johannesburg: “On one side the Covid ward is overwhelmed with cases. On the other side people are lined up as part of the Phase III trials of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

“Cyril Ramaphosa wants to have the entire population vaccinated by the end of this year,” McDermott said. “Now that we are in the second wave, there is more anger directed at the perceived injustice.”

“Since there is a shortage of vaccines, there will be competition,” said Edward Carr, deputy editor at The Economist. “The distribution of vaccines will control how many die.”

Distribution is a complex issue because only rich nations have the number of cold storage systems needed for the vaccines. “We might see a horrible scramble such as in the early days of the pandemic,” when nations requested bulk shipments of personal protective equipment.

Loder described some hits and misses for the funding of vaccine development. The European Union funded the Sanofi vaccine, “which hit a hurdle.” She also noted, “Canada’s bet paid off and they are in a position to donate vaccine earlier.”

COVAX, “the vaccine-buying club has promised to deliver 20 percent of each country’s needs.”

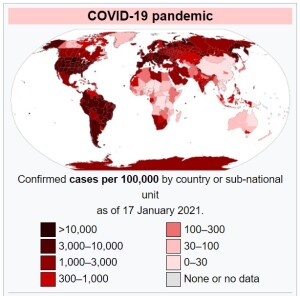

“This is not a rich-country disease,” Loder said, “but it has hit them harder since they have the older demographic that is hit harder by the disease.” The worst off are the middle-income countries with older demographics such as Latin American countries.

“The COVAX plan is to get three percent of each country vaccinated,” said Carr. “These are the health care workers and some essential services.” This will be a test of organization and cooperation.“Even India, which manufactures massive amounts of vaccine, will have trouble rolling out vaccines.”

McDermott said South Africa sees the vaccine distribution as a repeat of the HIV-AIDS epidemic. “This area was most affected by HIV-AIDS, and it took years for the treatments approved in North America to reach South Africa.”

Governments are keenly aware of the economic fallout, especially the debt relief needed for certain economic sectors. “The West wants to protect the current global order,” said Carr, “but it is being further tested by Russia and China.”

The pandemic battle has required people to trust in their governments. People must have trust in the vaccine-approval process. Now politicians are asking people to go along with the decision “to delay the second jab,” Carr said.

“Vaccines are all about trust,” said Loder. “The trials show the ideal case is two doses for best protection. … The best individual choice is still to take the vaccine” when offered, even if the timing of the second dose is uncertain.

Loder said vaccine hesitancy varies from nation to nation. “France is more skeptical about the vaccine.” Leadership is important. “In Bahrain and the UAE, the leaders have already rolled up their [shirtsleeves for vaccines].”

“Vaccine hesitancy has two components,” said Carr. “There are the hard-core anti-vaxxers, and then there are the more fluid types whose skepticism changes depending on the death rates and the information available.”

The media also has a role to play in the levels of trust around the vaccine. Loder cited, as an example, the vaccines developed in Russia and China. These vaccines did not go through the standard pathways to check. “However, I say these vaccines are ‘unproven’ – not that they are ‘unsafe’.”

The World Health Organization is considering sending the Chinese version of the vaccine around the world.

Once the healthcare workers are all vaccinated, the question becomes: how to balance lives versus livelihoods. “The lockdowns have involved trade-offs,” Carr said. “Do you open schools or bars?” He said there was a broad commonality: “The places with high Covid rates have the worst economies. People are afraid to go out.”

The converse is also true. “Taiwan had hardly any Covid, and their economy is currently booming.”

When asked about the effect of mutations, Loder said she could not predict. “This type of virus may continue to rattle around the world for a few more years. … It’s hard to say if we will require annual coronavirus shots.”

Vaccination passports are counterproductive and will undermine trust in the government, said Carr, “although the corporate sector may consider it.”

“Various countries ask for quarantine,” said Loder. “The passport will be a way around having to spend time in quarantine.” She said proof of vaccination will likely be required for cruise ships, “which are like floating petri dishes filled with 60, 70, 80-year-olds.”

She predicted that long-term care facilities will likely require vaccination passports for workers, to ensure workers don’t bring coronavirus in to the vulnerable populations. ♠

The vaccine passport shown in the last graphic is for yellow fever.