As the low-carbon energy transition takes hold, transition risk becomes a hot topic. Various uncertainties, mismatches, and potential obstacles emerge, threatening to delay the changeover. For example, in 2021, the U.K. had to restart coal-fired power plants due to low wind power.

Two major transitions in electricity generation are underway. The cost of generating electricity with natural gas has dropped—and the costs of solar panels and energy storage have also dropped. Both are leading to new vistas in power generation. However, “over-investment in CCNG may affect the transition to renewables,” said Gautam Gowisankaram, professor of economics at Columbia University and associate with Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). CCNG refers to combined-cycle natural gas power plants.

He was speaking at a webinar on November 21, 2024, presenting results from his article “Energy Transitions in Regulated Markets,” co-authored with Ashley Langer and Mar Reguant through the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). His presentation was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics (VSCE).

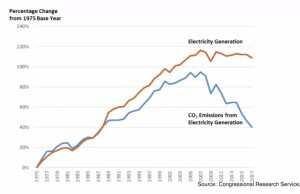

Decades earlier, a different transition occurred. He studied that previous transition to see what lessons could be learned and applied to our current situation. Over the years 1975 to 2017, U.S. electricity generation became cleaner, due to improved natural gas technologies. Over the same period, natural gas fuel prices were declining. Innovations meant natural gas fuel costs became cheaper than coal, and this led to a transition from coal to gas capacity.

Gowisankaram provided historical context for regulation. In the context of electricity, regulation has two main goals: power system reliability and affordability.

Electricity is viewed as a natural monopoly and is regulated in much of the U.S. There are high fixed costs to build a power plant and low marginal costs. Generally, rate-of-return regulation is used to limit the exercise of monopoly power. This means the regulator grants the utility a monopoly to provide the service—but makes sure to set a maximum price to cover costs and allow a fair rate of return on capital.

The regulator thus creates an incentive structure against which the utility optimizes, leading to known inefficiencies. “There is an incentive to invest too much in power plants,” he noted, “because utilities earn a rate of return on capital.”

The regulator’s task has become more complicated over the last 25 years due to new technologies, changing fuel prices, and increased environmental concerns. Furthermore, the regulatory structure is such that “the regulator can observe costs, but not the costs of alternative choices,” he said. “This leads to broad asymmetric information issues.”

To mitigate the problem of overinvestment, regulators require that the investments be prudent. Utilities may thus continue to run old technologies to prove that old power plants are “used and useful,” leading some citizens to wonder why dirty technology is still being used, as the following headline shows.

Gowisankaram and co-authors asked: “How does the current regulatory structure affect energy transitions relative to a cost minimizer? And a social planner?”

[Ed. Note: “Cost minimizer” is a hypothetical decision-maker who attempts to reduce costs, regardless of impact. “Social planner” is a decision-maker who attempts to maximize some notion of social welfare.]

The authors developed a dynamic structure model of electric utility regulation. This model considers operations decisions, capacity investment, and capacity retirement.

Then, with their estimated model, they simulated the impact of alternatives to rate-of-return regulation. He described the data and reduced-form evidence, gave the structural estimation approach, presented the results and the counterfactuals.

“The current regulatory structure created unintended incentives to use more coal,” he said. After running the two set-ups—cost minimizer vs social planner—they found that “the cost minimizer virtually eliminated coal capacity in the 30 years after natural gas prices fell, while the social planner essentially stops using coal immediately.”

“A broader takeaway is that the cost minimizer, social planner, and return-on-rate with carbon tax may require transfers for reliability.” This is consistent with subsidies in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

Further discussion and detail on the lessons learned from transitions in the regulated energy market may be found in their paper. ♠️

The graph above is from the VSCE presentation based on the cited article, “Energy Transitions in Regulated Markets”. Permission pending.

The thumbnail image is a detail from JPxG, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons, under the entry “Natural gas power plant.”