How can monetary policy achieve price stability and full employment objectives in the midst of a changing economic environment? Lately, the US Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) has been thinking hard about new ways to control inflation, given the new economic headwinds.

“Persistently low inflation presents a new problem for monetary policymakers,” said Mary C. Daly, president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF).

On August 29, 2019, she gave a speech to a conference of economists and policymakers in Wellington, NZ. This was a significant venue, because inflation targeting was pioneered in New Zealand in 1990, when “central banks around the world needed to tamp down rising inflation,” she noted. “We’re fighting inflation from below our target,” whereas two or three decades ago, inflation tended to climb too high, so was always being fought from above.

On September 3, 2019 the FRBSF posted the background to Daly’s speech as the article “A New Balancing Act: Monetary Policy Trade-offs in a Changing World.” It’s an excellent summary.

Daly contrasted the economic climate from earlier times with 2019. She said that, at the outset of her tenure in 1996 at the FRB, there were three givens:

- the potential growth rate of the U.S. economy averaged around 3.5 percent.

- the real neutral rate of interest, r*, was mostly in the range of 2 to 3 percent.

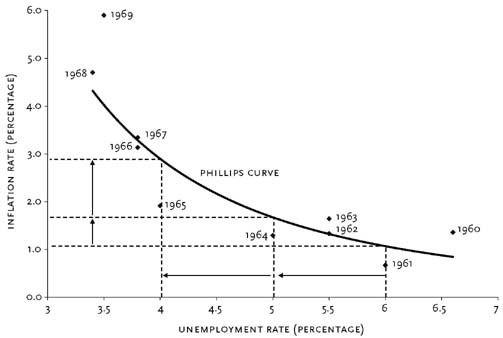

- unemployment and inflation were strongly linked through the Phillips curve.

In 2019, these first two numbers have shrunk. Potential growth rate stands at 1.9 percent and the real neutral rate of interest hovers around 0.5 percent. And worse, “the relationship between unemployment and inflation has become very difficult to spot,” Daly said.

“If the normal tension between unemployment and inflation has weakened,” she asked, “how do we know whether we’ve achieved our full employment mandate?”

Researchers at FRB have found some positive news: “when the unemployment rate drops below what is thought to be its long-run sustainable level, the benefits to marginalized groups increase.” Perhaps it is too much of a good thing: some young workers may be lured into the labour force before they finish their schooling.

“The most effective tool at our disposal is traditional interest rate adjustments,” Daly said. Corporations may be lured to make poor decisions. “If interest rates get too low, and borrowing becomes too easy, imbalances in financial markets could once again develop,” Daly cautioned. “I’m closely watching the high level of corporate debt.”

Achieving inflation targets is important for business, social, and economic planning. The FRB did not like to constantly miss their 2 percent goal (although a persistent miss can also be planned around). Daly wanted the reserve bank to have suitable wiggle room. “Below-target inflation translates directly into less policy space to offset negative economic shocks.”

Daly noted that the tool of flexible inflation targeting “worked well when inflation shocks were tilted to the upside.”

There are alternative strategies, such as “average inflation targeting,” and the two-pronged “price-level and nominal income targeting” that New Zealand has moved toward. These new strategies will “ensure inflation misses balance out over time,” Daly explained.

For the future, Daly emphasized, “we must adapt our monetary policy frameworks to deliver on the mandates we’re committed to: full employment and price stability.” ♠️

The article this posting is based on can be found at: https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2019/september/new-balancing-act-monetary-policy-tradeoffs-changing-world/

The images are from: AllPosters.com, 123rf.com, and economicsdiscussion.net.