How often have you heard someone scoff at the changing global temperature? “A two-degree increase? Heck, it changes by twenty degrees some days—and I don’t complain,” they say with a laugh.

“Is local temperature an incomplete representation of climate change?” asked Adrien Bilal, Assistant Professor of Economics, Stanford University. He posed the question at a webinar on October 3, 2024, which was part of a series of talks, the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics, sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

“Is local temperature an incomplete representation of climate change?” asked Adrien Bilal, Assistant Professor of Economics, Stanford University. He posed the question at a webinar on October 3, 2024, which was part of a series of talks, the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics, sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

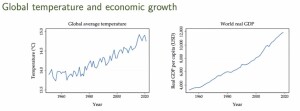

The global average temperature has been increasing over the time period 1950 to 2020 (data from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), as has the world real GDP (data from Penn World Table). The graphs below show, roughly, increases of about 1.5 degrees C in global temperature and $8,000 USD in global GDP over the 70-year period.

“Climate change is often portrayed as an existential threat,” said Bilal. “Yet empirical estimates imply a small loss in GDP for every one degree of global warming.” He decided to take a closer look at the empirical estimates—and found they focused on within-country, local temperature panel variation. His report is summarized in a recent paper titled, “The Macroeconomic Impact of Climate Change: Global vs. Local Temperature.” His co-author is Diego R. Känzig of Northwestern University.

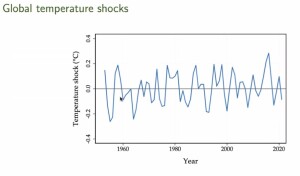

Since “general trending” might bias the estimated effect of temperature on output, the researchers decided to focus on temperature shocks. “Solar cycles and volcanic eruptions drive variation around the temperature trend,” Bilal said, “in addition to internal climate variability.” There were also persistent climatic phenomena such as El Niño events to account for.

Note the global temperature shocks over seven decades, shown below, never deviated more than 0.3 to -0.3 degrees C within that period.

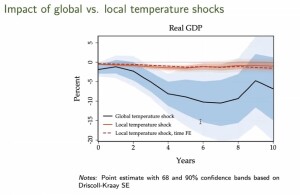

Their paper provides macroeconomic estimates of the impact of temperature, through a novel focus on global temperature rather than local temperature. Using natural climate variability and time series variation, they concluded that a 1-degree local temperature rise only implies a 1.5 percent decline in GDP. However, a 1-degree global temperature rise would imply a 12 percent decline in world GDP.

The social cost of carbon is an estimate, in dollars, of the economic damages to society that would result from emitting one additional ton of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Bilal and Kantzig quantified the social cost of carbon and the welfare cost of climate change using reduced-form impacts to estimate the damage function in the neoclassical growth model.

Bilal and Känzig reconciled this apparent discrepancy in global temperature (shown in blue, below) and local (red) temperature estimates. “Global temperature shocks predict a strong rise in damaging, extreme events,” Bilal explained. “Local temperature shocks do not.” Their paper goes into more detail, but as the graph below shows, the estimates using only local temperature underestimate the severity of climate change.

In conclusion, one counter-intuitive thing to bear in mind is that “average global temperature” is very different from “local temperature,” even though they are both expressed in degrees Celsius. ♠️

The graphs above are from the presentation based on the working paper. Permission pending.