How sustainable is a consumer good, like a car? Looking back at the intermediate goods produced during the stages of getting to that final good, such as the motor to put into the car, how sustainably were those intermediates produced?

Windmills are considered more environmentally friendly than gas power plants. But windmills require steel, which is a highly emission-intensive product. Hence, we also need to switch to environmentally friendly steel. This is but one example of “greening” the supply chain—how the green transition requires switching from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources not just at the end, but all along the production chain.

“There is a growing consensus worldwide that we need to speed up the transition,” said Philippe Aghion, professor of economics at Institut européen d’administration des affaires (INSEAD). “In this paper, we develop a model of ‘greenification’ along a supply chain. In each layer, an economic good is produced with a dirty technology, or… with a clean technology.”

Aghion was speaking at a webinar on December 19, 2024, presenting results from his article “Transition to Green Technology along the Supply Chain,” co-authored with Lint Barrage (at ETH Zurich and CEPR), David Hémous (at University of Zurich and CEPR), and Ernest Liu (at Princeton University and NBER). His presentation was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics (VSCE).

“Our model displays cross-sectoral complementarities,” he said, “similar to other models such as the Big Push.“ The Big Push model emphasizes the fact that a firm’s decision whether to industrialize or not depends on the expectation of what other firms will do.

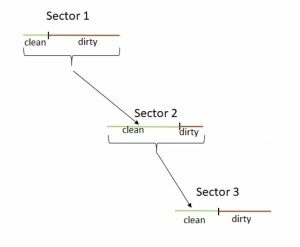

In Aghion’s model of green technological transition along a supply chain, summarized in the figure below, each layer produces a good which is an aggregate, produced using either a dirty technology which uses only labor, or a clean, “electrified” technology which uses labor and the good produced by the next upstream layer in the chain.

Details of the assumptions, calculations, and counterfactuals may be found in the article “Transition to Green Technology along the Supply Chain.” He discussed four implications from the research to date.

Interesting Implications

- Limited and temporary sectoral subsidies can have large, long-run effects.

- The social optimum requires both a carbon tax AND sector-specific targeted subsidies.

- A government which is constrained to focus its subsidies to electrification of one particular sector, should primarily target downstream sectors.

- Overinvesting in electrification in the wrong upstream branch may derail the overall transition towards electrification downstream.

“The greenifications across sectors are strategic complements,” he noted. In economics, the decisions of two players are called strategic complements if they mutually reinforce one another. Hence the modeled economy “features multiple steady states.”

Finally, he noted that they applied a two-layer version of their basic model to iron and steel production, and showed that, despite using a uniform carbon price, the economy could get stuck in a “wrong” steady state with CO2 emissions way above the social optimum.

He concluded with several suggestions about how the model could be extended. ♠️

The supply-chain schematic above is from the VSCE presentation based on the cited article. Permission pending.

The image of wind turbines is from Energy Education.

Click here to access the paper by Aghion et al. titled “Transition to Green Technology along the Supply Chain.”