Shadow banking has enjoyed extraordinary growth over the past decade, especially in the emerging markets of China. The implications were discussed in the webinar “Shadow Banking: Standing at the Precipice?” sponsored by the Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP) on August 6, 2019.

Cindy Li, a Greater China analyst of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, was the second of two speakers at the one-hour GARP webinar. She said the shadow banking system in China has evolved to a fairly large group of powerful competitors, but that has led to “a build-up of risk” as China’s economic growth slows down.

First, the basics. What, exactly, is shadow banking? She quoted the full definition of shadow banking used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF): “Nonbank financial intermediaries that provide services similar to traditional commercial banks, but are not regulated or supervised like banks. These can include hedge funds, money market funds, and structured investment vehicles (SIVs), depending on their investment and funding strategies.”

Different types of credit-based intermediation exist in different countries and, thus, “shadow banking entities look quite different in different countries,” she said.

How big is China’s shadow banking system? The size is estimated using the bottom-up approach, with adjustments to remove double-counting. “It is more art than science,” Li admitted. She showed estimates from four organizations that had tried to estimate the size: global management consulting firm Oliver Wyman (from their 2015 report), the Hong Kong-based think tank Fung Global Institute (2016), Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2015), and Swiss investment bank UBS (2016).

Estimates of the size varied wildly. The first two organizations estimated a size of about one-half of the Chinese GDP. The FSB estimated about one-fifth of the GDP, whereas USB estimated 80 percent of the GDP.

“In recent years, its growth has been a cause for financial stability concern,” Li said. She showed a graph of shadow banking growth around the world, from 2012 to 2017.

China has financial system interconnectedness that is becoming ever stronger. There is a potential spillover of shadow banking effects into the regulated banking sector. Shadow banking activities have grown in complexity, she noted, referring to an example of SIVs and a trust company. As a side note, she wryly commented, “an increasing use of acronyms may be an indication of increasing complexity.”

“They use layers to circumvent regulatory pressure,” Li said. “There are a lot of potential moral hazards here.”

Li provided an “incomplete list of regulatory efforts to rein in shadow banking activities.” Chief among them is building a firewall between shadow and regulated banking.

In the Q & A session, Li commented on the relationship between financial technology (Fin Tech) companies and shadow banking. “FinTech serves as a catalyst,” she said, pointing to Alibaba’s money market fund, which is currently very large.

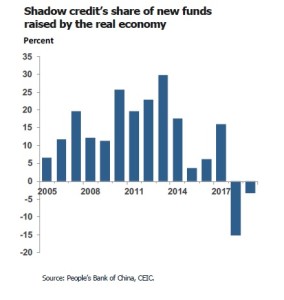

“Shadow banking’s importance is declining” since 2017, Li said, now that the double-digit growth in China has abated. “There’s a trade-off between financial stability and economic growth.” ♠️

Click here to view the one-hour webinar presentation.

The graph shown is from Cindy Li’s portion of the webinar presentation; permission pending.

Click here to view postings by Cindy Li at FRBSF.

Click here to read about the presentation by the first panellist, Fabio Natalucci.