The Covid-19 pandemic has caused supply chain disruptions. How much have the costs of international trade increased? What impact has this had on the U.S. economy? What is the effect on labor force participation? Can existing models properly quantify these effects?

Recent research by three leading economists tried to model the real-life situation of U.S. dependence on a global supply chain and what happened when parts of that chain were broken. (“Broken” encompasses several scenarios: “ports being closed or operating at partial capacity, fewer workers being available for health reasons, and a shortage of shipping containers, among other challenges.”)

On January 19, 2023, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF) released a report, “Supply Chain Disruptions, Trade Costs, and Labor Markets.” The authors are Andrés Rodríguez-Clare, Professor of Economics, at University of California at Berkeley; Mauricio Ulate, Senior Economist, FRBSF; and Jose P. Vasquez, Assistant Professor, London School of Economics.

They used an extensive framework to link international trade and unemployment, incorporating 87 regions—50 U.S. states, 36 other countries, and an aggregate rest-of-world region—and 15 economic sectors. It included trade costs for shipping products between countries. In contrast to standard models that assume full employment, “our framework incorporates the possibility that unemployment could increase after economic disruptions,” they write.

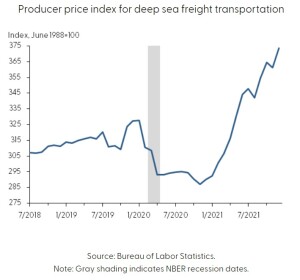

To model the increased costs of moving goods and services, they used a proxy. The producer price index of deep-sea freight transportation services rose about 12 percent over the course of the pandemic, as shown in the chart below.

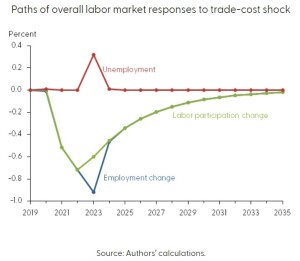

They used this input to model the percentage change in employment, the percentage change in labor force participation, and the unemployment rate, all labelled in the chart below. (These are cumulative percentages since 2019.)

Unemployment does not occur right away at the time of the supply chain disruption; there is a time delay. They write, “Our model does not project that the low point for employment will happen until 2023, due to the additional unemployment that is generated when the trade-cost shock dissipates.”

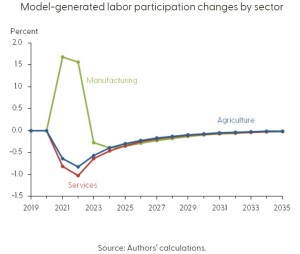

Their model allows them to compare the impacts of trade disruptions on different economic sectors. The pandemic had some effect on the availability of service workers, but a greater effect on manufacturing sector workers, as shown in the chart below.

The authors explain the rise in labor participation in the manufacturing sector. “First, there is a general decrease in demand due to the fall in overall employment, reflecting that spending power drops when people are out of work. Second, foreign inputs are more expensive, making production less efficient and decreasing labor demand. Third, there is an “expenditure-switching” effect across countries: imports become more expensive and tend to be substituted with local production, increasing labor demand in net-importing sectors.”

The authors caution their model does not include pandemic-related phenomena such as pent-up demand (the strong return to consumerism following a period of decreased spending), and fiscal support.

They conclude they found “a temporary but long-lived fall in labor force participation” due to the pandemic. “Second, there is a temporary increase in manufacturing employment. Third, unemployment is generated mostly around the time when the trade disruptions disappear.” ♠️

Click here to read the full report.

All figures are from the FRBSF Economic Letter; permission is pending.

The colorful graphic on supply chain management is from TechTarget.com.