Climate change marches on. To prepare for worse storms, droughts, and wildfires, the infrastructure must be improved. Governments have different ways to handle the costs of adapting to climate change. How will these additional costs be borne?

“Transition to a carbon-neutral economy is at the top of the policy agenda around the globe,” said Moritz Kuhn, professor of economics at the University of Mannheim. Private households account for about two-thirds of carbon emissions. “Governments can introduce policies to speed up the adoption of green technologies,” he said, but the heterogeneity of consumption and carbon emissions could present problems. These will be unevenly distributed.

Kuhn was speaking at a webinar on November 7, 2024, presenting results from his article “Distributional Consequences of Climate Policies,” co-authored with Lennard Schlattmann at the University of Bonn under the auspices of Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), a European organization. His presentation was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics (VSCE).

“Little is known about the quantitative consequence of policy trade-off between carbon emission reduction and redistribution,” he noted.

There is now a database that contains microdata on the heterogeneity of carbon emissions in the German household sector. Economists can look at infrequently adjusted goods (such as cars, which may be bought once every five to ten years) and what are known as commitment goods (such as gas and oil to run that car, which are bought more frequently).

In purchasing big-ticket items such as a car, the consumer must decide what technology to adopt, and might only be able to afford “dirty tech.” Gas-powered cars are, on average, less expensive than electric vehicles (EVs). But once the decision is made, the consumer does not decide each time: “Do I buy a liter of gas or a kilowatt of electricity?” No, they are locked into paying for commitment goods, namely, the fuel that is appropriate for the vehicle they have chosen.

To understand the trade-off between reduction and redistribution, Kuhn and Schlattmann developed a life-cycle model guided by empirical evidence, looking at a mix of green and dirty household technologies. They studied the transition period 25 years into the future, comparing policy mixes.

For the carbon emissions data, they used the multi-region data Exiobase, which has data on carbon emissions for 102 different consumption goods. “Carbon emissions include direct and indirect emissions, such as from transportation,” he noted.

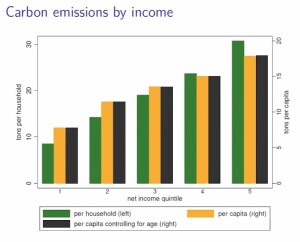

Empirical results confirmed there is an increasing carbon footprint with income. The chart below shows the data divided in five parts according to net income. The top quintile emits four times as much per household as the bottom quintile. Also, the top quintile emits twice as much per person as the bottom quintile.

“Consumption commitments such as cars and heating systems account for 35 percent of emissions,” they found. Independent of income, consumption commitments are only 11 percent of emissions.

Their model results show that a proportional subsidy for green tech was most effective in reducing carbon emissions.

“The single, discrete adoption decision for commitment goods makes the carbon tax ineffective,” Kuhn noted, “and this affects disproportionately more infra-marginal consumers.”

They found that “household heterogeneity induces policy trade-off between the speed of emission reduction and redistribution during the transition period.” Progressive tax financing avoids redistribution and leads to strong emission reduction.

The report concluded, “If the subsidy is financed by a progressive income tax, it yields a policy mix that leads to rapid emission reductions and a majority of households supporting its distributional effects.” ♠️

The graph above is from the VSCE presentation based on the cited article. Permission pending.

Click here to access the article “Distributional Consequences of Climate Policies.”