Question 1. Do you think that one’s belief system triggers one’s actions? Or does one act and then justify one’s actions by changing one’s beliefs?

Question 2. Is an effective leader one who adheres to a constant belief? Or is the effective leader one who adheres to “situational ethics”?

These are two dilemmas that were explored in more depth on February 8, 2022, when Kevin Veenstra, Associate Professor at De Groote Business School at McMaster University, presented a virtual workshop on ethical decision making to members of the CFA Society Toronto.

Veenstra’s research focuses on personality and unconscious motives and features some intriguing titles. Among his published papers are: “Welcome to the Gray Zone: Shades of Honesty and Financial Misreporting” and “Is Sin Always a Sin? The Interaction Effect of Social Norms and Financial Incentives on Market Participants’ Behavior” as well as an article on a recent case of fraud, “Home Capital Group – The High Cost of Dishonesty.”

“The goal of ethical training,” he said, “is to encourage you to be more conscious about thoughts and behaviours so you are more likely to act on ethical issues before they become a problem.”

Veenstra observed that in the academic environment, cheating has become more widespread during the Covid-19 pandemic, as everything about classes, including exams, had to move online.

“There is a difference between legal and ethical choices,” he said. “Some things are legal but not ethical.”

Human personality develops morality in three phases: learning to feel guilt and shame; learning social development; and then learning how to see things from the perspective of another.

In the nature versus nurture debate, experts debate the degree of inheritance of the “Big 5” personality traits:

- openness to experience (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious)

- conscientiousness (efficient/organized vs. extravagant/careless)

- extraversion (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved)

- agreeableness (friendly/compassionate vs. critical/rational)

- neuroticism (sensitive/nervous vs. resilient/confident)[4]

To this he would add a sixth dimension, honesty and humility. In general, “honesty is innate. Your genetics influence this trait.”

He asked the webinar audience to take the 10-point questionnaire, Ethics IQ, developed by Steven Mintz. Then the audience broke into groups of 3 or 4 people and discussed the two questions given at the very beginning of this posting. Regarding the first question, after the groups reported back, he said, “Most people say their actions are some combination of the two. You do tend to rationalize cognitive dissonance.”

Regarding the second question, he said, “someone who engages in situational ethics tends to be low on ethics, because they’ll do what’s best for them, not the group.”

Even in teaching, Veenstra said, a professor feels pressure to cater to students in order to gain a good rating—this can encourage a form of “situational ethics.”

Five ways to slip up

Veenstra listed five circumstances that might influence a person to engage in unethical conduct:

- Incrementally engaging in unethical behaviour – We subconsciously lower our standards over time through small changes. Excuses like: “I was just one mile over the speed limit…” become “I was just three miles over…” and so on.

- Obedience to authority – We are more likely to act in unethical ways when requested to by a supervisor.

- Conformity bias – We become acculturated to behaviour and assume that it is normal and acceptable.

- Over-confidence in ability to act appropriately – We tend to over-rate our own honesty and fair-mindedness.

- Rationalizations – We may feel cognitive dissonance and therefore change our beliefs—or our actions—or the perception of our actions.

Giving Voice to Values

Veenstra referred to the initiative launched by Mary Gentile, Professor at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia: Giving Voice to Values (GVV). Gentile is author of the book of the same name, and she has also spearheaded the roll-out of the Giving Voice to Values program at the CFA Institute.

GVV is not about persuading people to be more ethical. “Instead, it starts from the premise that most people want to act on their values, but they also want their actions to be successful and effective,” says the CFAI website.

“Decision-makers need to find a way to effectively articulate personal and professional values,” Veenstra said. He briefly outlined the brainstorming exercise that Gentile recommends. “What if you wanted to do the right thing?”

- Purpose – what is the plan; what is your belief system? Think about this well in advance so it is there to guide you, like a mission statement

- Self-knowledge and alignment – avoid emotional, spur-of-the-moment interactions

- Values – nobody should disagree with the shortlist of values: honesty, compassion, respect, and fairness.

- Choice – what has helped or hindered in the past?

- Normalization

- Voice – give voice to ethical behavior. This is at the heart of this method. If you need to have a difficult conversation about ethics, script it out in advance. “Take a couple of days, de-escalate the situation, think carefully about what you say.”

- Reasons and rationalization

Firms must take action against those who violate their integrity, and they must reward those whose careful actions, often going unnoticed, preserve it. ♠️

Click here to sign up for Ethical Decision Making: a 1.5 hour course for members of CFA Institute.

CFA Institute Ethics Learning Lab

https://cfainstitute.nomadic.fm/signin

Ethical Decision-Making Program

PL credit:1.5 (SER credit:1.5); approximately 1.5 hours to complete

https://www.cfainstitute.org/en/ethics-standards/ethics/ethical-decision-making

GVV for Investment Professionals

PL credit:1.5 (SER credit:1.5); approximately 1.5 hours to complete

https://www.cfainstitute.org/en/ethics-standards/ethics/giving-voice-to-values

Ethical Decision Framework

https://www.cfainstitute.org/-/media/documents/support/ethics/ethical-framework-guide.ashx

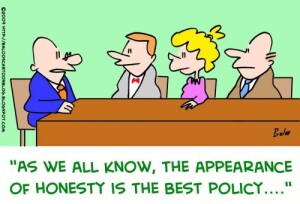

The ‘appearance of honesty’ cartoon is from the website Baloo Cartoons. Permission pending.