More workers than ever before are being exposed to heat stress worldwide, according to a 2024 report. Heat stress has a knock-on effect for productivity and thus the gross domestic product (GDP). How much does a permanent rise in temperature decrease the GDP? Economists have tried to estimate the size of the climate change effect, in variously affected countries, with different models and different assumptions.

“There’s a wide divergence in projections of how the GDP will change depending on climate change,” said Valery Ramey, Senior Fellow at Hoover Institution and Research Associate at National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). She was speaking at a webinar on September 19, 2024, presenting results from the working paper titled “How Much Will Global Warming Cool Global Growth?” Her co-authors on the working paper are Ishan Nath, at FRBSF, and Peter Klenow, at Stanford University and NBER.

The presentation was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics (VSCE).

“The prevailing literature shows modest impacts,” she noted, such as Barrage & Nordhaus (2023) who predict a 1.6 percent drop in GDP from 3֯ C global warming. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimate (2014) predicts a 0.2 to 2 percent drop in GDP from 2֯ C global warming.

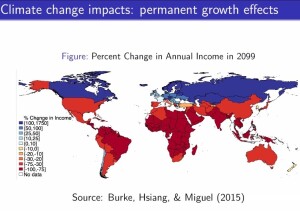

However, a prominent exception, Burke, Hsiang and Miguel (2015), predicts very large effects, “with a 23 percent drop in GDP.” This leads to climate change ultimately reducing incomes by “more than 80 percent in half of all nations.”

“Damage estimates are highly influential,” Ramey said, so different institutions approach the problem from different angles. Macroeconomists add a climate damage component to their models. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Interagency working group considers the social cost of carbon estimates. Policy institutions such as the IPCC, EPA, World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) all took a crack at estimating the damage, as well as advocacy groups such as the Cato Institute and Sunrise Movement.

Impact estimates diverge, she said, because we don’t know “if a permanent increase in temperature affects long-run economic growth or levels.”

One study from 2015 found that only Russia, Canada, northern Europe, and Chile would have an improved annual income in 2099 due to the permanent growth effects of climate change.

“The key challenge is interpreting the impact of a temporary temperature shock” as time wears on.

The working paper presents theory and evidence for why country growth rates should not permanently diverge; provides new estimates of the temperature-to-GDP relationship; and makes projections of future climate change impacts based on empirical persistence of temperature effects.

“Our model estimates suggest growth is linked across countries,” she said. “A permanent increase in temperature will lead to a temporary growth effect,” she noted. “And a trending temperature—such as we see for climate change—leads to a persistent growth effect.”

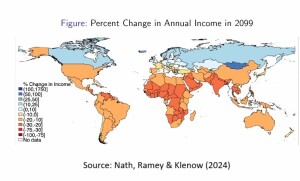

Nash, Ramey and Klenow project that current “global warming trends will reduce global GDP by 6 to 12 percent by the year 2100.”

“This is not a comprehensive welfare estimate,” she cautioned. It does not include the following:

- Non-market damages such as mortality and civil conflict

- Non-temperature effects such as hurricanes and coastal flooding

- Uncertainty and risk aversion

They used a stylized model of growth known as total factor productivity (TFP). TFP growth is defined as the amount of output growth that cannot be explained by growth of the individual factor inputs in the aggregate production function. “In the absence of shocks,” she noted, “countries converge to parallel TFP growth paths with a stationary distribution of relative TFP levels.”

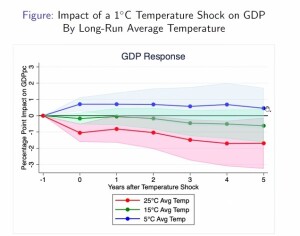

“We then use data from a panel of countries to show that temperature shocks have large and persistent effects on GDP,” she said, “driven in part by persistence in temperature itself.”

As the figure below shows, if a country has an average long-range temperature of 5֯ C, a temperature shock of 1֯ C will raise the GDP somewhat. If the country has an average long-range temperature of 25֯ C, a temperature shock of 1֯ C will reduce the GDP by about 2 percent.

She made a three-part case for global growth spillovers. Rich countries grow at similar rates despite innovation differences. Country level differences persist, but growth differences do not. Third, the frontier-country technology predicts global growth. They applied this method to spillover effects.

Further details on how the model accounted for other known trends may be found in the working paper itself. It has a three-part conclusion. First, the model and evidence suggest growth is tied together across countries. Temperature is unlikely to have permanent country growth effects.

Second, dynamic estimates show persistent effects of temperature on GDP. There is a moderate persistence of temperature itself.

Third, and last, projections suggest warming reduces global income by 6 to 12 percent by the year 2100. “This is 3 to 5 times larger than permanent level effects.” Ramey said, “This is 3 to 4 times smaller than the permanent growth effect. The country-specific effects differ even more dramatically.” ♠️

The figures above are from the report. Permission pending.

The photo of the heat-stressed worker is from the International Labour Organization, Heat at work: Implications for safety and health.