What will be the effect of Basel III on banks in emerging markets? “Commercial banks will become less interested in providing loans,” said Dr. Michael C. S. Wong, the first panellist in a webinar on Banking in Emerging Markets held November 20, 2014, and sponsored by the Global Association of Risk Professionals. He is Associate Professor of Finance at City University of Hong Kong, and Chairman at CTRISKS Rating.

Wong summarized the challenges of the new Basel III regulatory regime, with its tougher capitalization and liquidity requirements. A global systemically important bank (G-SIB) will have additional capital and cash-holding requirements, he said, and “will be unwilling to make loans.”

China has one G-SIB and four domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBs). [Editor’s note: The Financial Stability Board publishes a list in November of each year; the Wikipedia list of G-SIBs and D-SIBs shows the breakdown by country.] Wong said the D-SIBs “will face the same reality” as the G-SIBs.

Thus, the activity in banking “will shift to fee-based activities,” said Wong. “Operational risk will increase in importance.” The banks will begin to lose their lending function, and “the banks will allocate resources to good borrowers,” he predicted.

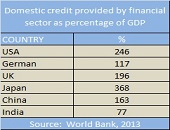

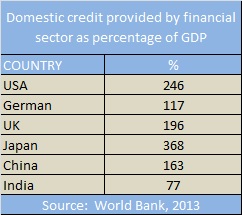

The domestic credit provided by financial sector as percentage of GDP was a cornerstone of Wong’s comparison of developed versus emerging markets. (See accompanying figure based on World Bank statistics for 2013 using the gross domestic product as a yardstick.) China and India are on the low side for providing domestic credit.

During the question period, a member of the audience asked what the optimum level of domestic credit should be. Wong opined that the levels for China and India could be higher than present. Moorad Choudry (second presenter) said credit levels were a “double-edged sword.” Iceland had domestic credit levels around 300 percent of its GDP when it reached a severe financial crisis. “The minute the economy starts contracting, it is a house of cards… [credit levels] should not be so far beyond the GDP that the country can’t bail out its banking sector.”

“Enterprises big and small face the reality they can’t get credit,” said Wong, noting that only about half the domestic credit was in the form of non-government loans. If China liberalizes the interest rate market, greater funding instability will lead to even fewer loans being made.

To combat credit tightening, Wong suggested that governments of emerging markets could do more to support corporate bonds and securitization of bank loans. They could also “develop specialized banks for high-risk lending” for the small to medium enterprises. “They could regulate and support shadow banking.”

Wong painted a thought-provoking picture of commercial banks in China in the future, when transactional banking, or banking for fees, will become important and “lending will become a marketing gimmick.” He drew an analogy to current-day banks that maintain a trading desk primarily to provide this service to clients.

Chinese banks will also work more with other financial institutions such as insurance companies and pension funds. They would leave the lending to private equity concerns, money lenders and banks that are specialized in taking on higher credit risk for higher yield. ª

Click here to view the webinar presentation on banking in emerging markets. Wong’s section covers slides 5 to 11.