In 2003, a devastating heat wave in Europe killed an estimated 70,000 Europeans, many of them elderly people living alone. This, and a series of other extreme weather events, have persuaded many countries to take climate change seriously.

The European Union enacted the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). It came into effect as of October 1, 2023, and is designed to account for the carbon cost of producing imported goods, with the ultimate aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

“I’m a huge fan of CBAM,” Catherine Wolfram, professor of economics at MIT Sloan, said, joking that the name sounded like something one might find in a superhero comic. “CBAM creates an important incentive for trading partners with Europe to adopt carbon pricing.”

Wolfram was speaking at a webinar on January 16, 2025, presenting “The Economics of Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms for Lower-Income Countries,” a research project she is carrying out with co-authors Kimberly Clausing at UCLA, Jonathan Colmer at University of Virginia, and Allan Hsiao at Stanford University. Her presentation was part of the ongoing series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics (VSCE).

“There is a proliferation of carbon pricing around the world,” she said, showing a map of those countries using carbon tax and those using an emissions trading scheme (ETS), also known as cap and trade (CAT). Of the developed nations, only three have no form of carbon pricing: Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the U.S. (Click here to see a map of carbon pricing schemes by country.)

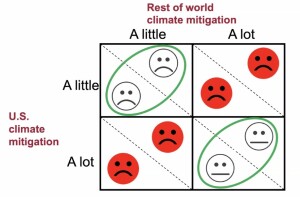

“Climate change is the world’s largest global collective action problem,” she said, “but without coordination, a country will take a free ride on other countries’ efforts. The costs of policy action are carried at home, while the benefits are shared worldwide.”

Wolfram said that climate change is trapping the world in a major prisoner’s dilemma because “every country would like other countries to take aggressive steps to mitigate climate change.”

She described the prisoner’s dilemma thought experiment, which involves two rational agents, each of whom can either cooperate for mutual benefit or betray their partner (“defect”) for individual gain. The dilemma arises from the fact that, while defecting is rational for each agent, cooperation yields a higher payoff for each. This figure illustrates the optimal solution for the prisoner’s dilemma.

“With CBAM, cooperation works,” she said, pointing out that two “neutral faces” were better than two “unhappy faces” as shown in the above schematic.

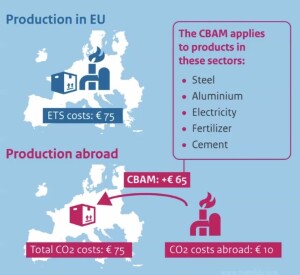

How does the CBAM work? “If a jurisdiction has a domestic carbon price for a good, such as the E.U. Emissions Trading System” has for its cost to produce steel, then CBAM makes an assessment at the border so that imports will also pay the same carbon price. The importer receives credit for any carbon price paid in the country of origin, as shown in the schematic below.

The CBAM applies to the industrial sectors producing: steel, aluminum, electricity, fertilizer, and cement. “If your country is not mitigating global warming, you will face the CBAM,” she said. Such regulation makes it easier to solve the coordination problem that occurs in the prisoner’s dilemma.

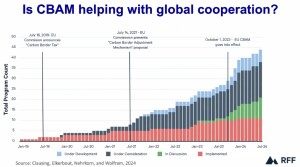

“Is CBAM helping with global cooperation?” she asked. It’s too early to tell, but clearly “the EU has started the global conversation on carbon pricing, as her recent work reported in a paper authored by Clausing, Elkerbout, Nehrkorn & Wolfram and posted at Resources for the Future (RFF) shows.

“The U.S. is out of sync with the carbon pricing conversation.” Wolfram showed two graphs of total media hits over the past eight years, where phrases related to carbon pricing were counted. Over the past eight years, the E.U. has had more media coverage about the issue than the U.S.

“Bottom line,” she said, “CBAMs can play an important role in galvanizing and enforcing climate action.”

However, there are concerns about the impact on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). There are allegations, she noted, of “regulatory colonialism.” For example, a 2024 report in The Guardian titled, “India seeks UK carbon tax exemption in free trade deal talks,” reports on this controversy over carbon pricing.

Wolfram used as examples her work on carbon pricing in the production of aluminum in Mozambique by the joint venture company Mozal, and also a case study in Turkey.

Wolfram and co-authors concluded that “primary aluminum plants in lower income countries do not necessarily have higher emission intensities. Equilibrium impacts (higher prices for clean suppliers) may even increase profits for lower income country plants.”

From the examples they were able to identify regulation and reallocation effects of CBAM. ♠️

The schematics above are from the VSCE presentation based on the cited article. Permission pending.

Click here to access the Future (RFF) paper coauthored by Clausing, Elkerbout, Nehrkorn & Wolfram.