Biologists have long known that biodiversity is the key to nature’s resilience. In a biodiverse world, if the environment changes and some organisms can no longer thrive, others can take their place and fulfil functions that are essential to the species’ survival, and ultimately, human survival. Even the lowliest animals play significant roles, such as insects that pollinate—and a third of the food we eat depends crucially on insect pollinators.

In addition to its intrinsic value, biodiversity underpins ecosystem services, providing the backbone of the global economy. Biodiversity loss, or the reduction in the genetic diversity of life forms, can lead to the collapse of entire ecosystems.

The biggest driver of biodiversity loss is how people use the land and sea, according to the U.N. Environment Programme (UNEP). Forests, wetlands, and other natural habitats are being converted for agricultural and urban uses. Agriculture and increasing urbanization occur, usually without consideration to the alien invasive species being brought in.

What, then, is being done to counteract biodiversity loss? And how well are these costs understood?

“Land use restrictions are the preferred policy tool to halt the dramatic decline in global biodiversity,” said Matthew Gustafson, professor of economics at Penn State University, “but their economic costs are unknown.” Gustafson was speaking at a webinar on January 30, 2025, presenting “The Biodiversity Protection Discount,” an article he co-authored with Golnaz Bahrami and Eva Steiner, who are also at Penn State University. His presentation was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics (VSCE).

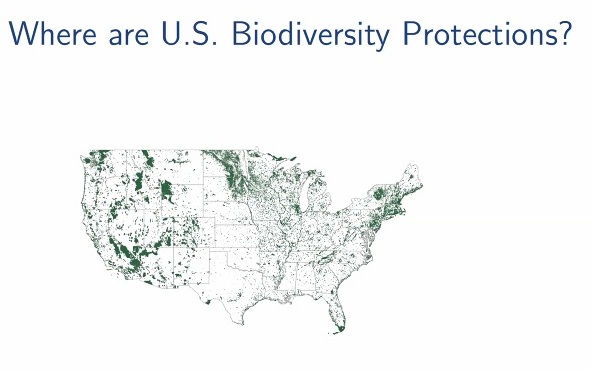

“Currently, eight percent of the land in the U.S. has restricted use,” he said. Such protections have costs. “Policy should weigh dispersed social benefits of biodiversity against private costs.”

“When you restrict land use, you destroy the option value of the land,” he said. In economics, option value refers to the cost placed on private willingness to pay for maintaining a public asset—even if there is little chance the individual will actually ever use it. For example, a city setting aside land for a city park is forgoing the municipal taxes that could be collected from that land. Option value is one element of the total economic value of environmental resources.

Gustafson and co-authors provide the first estimate of the biodiversity protection discount in the market for vacant land. They used regression discontinuity design (RDD) to distinguish between direct vs. indirect effects. Their analysis considered the distance to the border between neighboring lots that did not have restrictions. They also examined newly established protected areas.

Further details on their treatment, assumptions and results may be found in the original article.

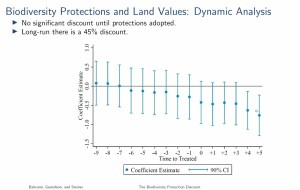

Their results shed light on private costs of land-use restrictions for biodiversity protections, and the economic relevance of typical U.S. biodiversity protection efforts. He noted, “We provide first evidence that biodiversity protections have a meaningful impact on vacant land practices, creating the biodiversity protection discount, closely linked to reduced development.” As the figure below shows, there was “no significant discount” until the protections were adopted (the “time to treatment” axis). And long run, they estimated a 45 percent discount (a coefficient estimate of 0.45).

They found the biodiversity protection discount “is larger in locations where developable land is more scarce and where political regimes are more committed to conservation. We quantify the costs of existing biodiversity protections at $820 billion or 3 percent of aggregate U.S. land value.”

The results by Gustafson and co-authors contribute to a growing body of work on welfare consequences of biodiversity conservation. To determine the optimal conservation policy, a thorough analysis would weigh these costs against the benefits provided by ecosystem services. ♠️

The graphics above are from the VSCE presentation based on the article, “The Biodiversity Protection Discount.” Permission pending.

The image of the golden toad in the thumbnail is from Wikipedia and is the work of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employee, taken or made as part of that person’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain. For more information, see the Fish and Wildlife Service copyright policy.