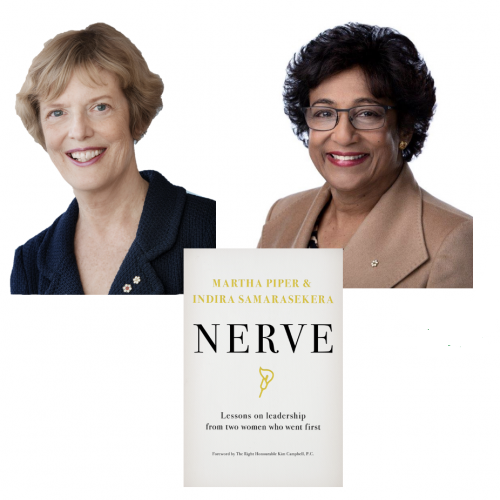

“We believe women need to confront their reluctance to consider a leadership role and work actively to counter it with a more positive response.” This clarion call is issued by two top leaders in the academic and corporate world. Indira Samarasekera was the first woman president of the University of Alberta, and a director of Magna International, TC Energy, and Stelco. Martha Piper was the first woman president of the University of British Columbia, and a director of the Bank of Montreal, Shoppers Drug Mart, and TransAlta Corporation. Although neither was born in Canada, both are officers of the Order of Canada.

“Women are notoriously ambivalent,” they write in their new book, because whenever a chance to lead comes up, women “identify all the reasons they should not or cannot step into the role.” They each have stories of turning down opportunities to lead. It was never their first reflex, to accept the mantle of leader. This reviewer was intrigued by this book on leadership, written by reluctant leaders—people I could identify with.

Nerve: Lessons on Leadership, published in 2021 by ECW Press, is meant to inspire the future generation of women to take on leadership roles. The authors speak candidly about their own experiences as they climbed the career ladder in surprising ways. In three parts, the authors look at how to develop the nerve to lead, how to actually be a leader, and finally, how to resume “ordinary” life after being a leader.

Are women born or bred to lead? These two heavy hitters begin with a big-picture question. They look at some hypotheses (birth order, family expectation, etc.) and compare them against their own lives. Nothing has perfect correlation. “Although various theories have been developed to explain who is suitable for leadership, we believe it is much more complex than any single hypothesis, particularly for women.” (p. 20)

What is the optimum education of a female leader? “Our view is that it really does not matter whether you choose to become an engineer or a physical therapist, as long as you are pursuing a career that you find interesting and challenging. …It is more important to discover how you learn rather than what you learn. Finding ways to feed your curiosity and foster creative learning is more likely to prepare you for leadership opportunities than studying [a particular subject].” (p. 38)

Is it possible for a top female leader to successfully combine career with marriage and children? Each author had two children; one has been married long-term and the other had an amicable divorce—“a dream divorce” she calls it. “Understand that it takes a great deal more nerve to leave an unhappy relationship…[divorce] represents a thoughtfully considered decision that is in everyone’s best interests.” (pp. 56-7)

When it comes to the decision to have children, they caution that “with all the planning in the world, your best-laid plans may not unfold. …you will not be able to truly understand the emotional attachment you will have for your newborn until you actually experience it.” (p. 57)

What is the role of luck in career development? “Few, if any leaders would suggest that they attribute their achievement solely to their pre-planned actions or undertakings. Instead, the record shows that serendipity or happy surprises have often contributed significantly to their critical decision-making and career choice.” (p. 70) They actively encourage the reader to stay on the lookout for happy coincidence: “unexpected and unplanned things will occur throughout your life that you will need to recognize for the springboards they present. How you piece together the breadcrumbs or clues will determine your reaction to these serendipitous events and where your career goes from there.” (p.71)

The authors draw a distinction between a mentor and a sponsor, the latter of which has not been as widely understood or promoted as the former. “However, a sponsor can have an enormous influence on one’s career trajectory, often more than a mentor. A sponsor… is a senior person who believes in your potential and is willing to take a bet on you; they advocate for your next promotion, encourage you to take risks and have your back. And they expect a great deal from you, namely stellar performance and loyalty.” (p. 67)

They advise, “Recognize that the self-doubt you experience when approached to lead is a normal reaction of women and not something unique to your particular experience.” Furthermore, “when working with male colleagues use caution in expressing your lack of confidence or reluctance to step up.”

They have a lot of solid advice on early days in a leadership role. “Practice patience… be prepared for increased scrutiny… work at active listening… and become a student of the history, traditions and culture of the organization.” (p. 108) Regarding the last point, Piper is admirably forthcoming about her own misstep when she became president of UBC and gave out baseball caps to a high-level delegation. “Do not expect the transition period to be smooth.”

How should a leader go about assessing, developing, and promoting the top performers? Here, it might sound like a drawerful of clichés: “Recognize that past performance is the best predictor of future performance… Keep an open mind… Recognize that newcomers will require additional support in orienting to the culture…. If the person is no longer performing at the level you expect, find the nerve to cut your losses.” (p. 128) But the clichés exist because they apply, time and again, to the choices a leader must make.

“The easy aspect to team building is identifying and recruiting the people,” they write. “Motivating the team and keeping them focused… is more difficult. … The best reward for outstanding performance involved personal recognition by the leader.” (p.109)

One of my favourite chapters is titled “Grit and grace: making things happen.” They open by explaining “Grit is what you do. Grace is how you do it.” (p. 131) They recommend that a leader occasionally review their tough decisions and the difficult situations they have encountered. “By recollecting these experiences, you will gain confidence that you have the nerve to lead.” (p. 151) This is storytelling to oneself, and when it is broadened to the organization, it becomes immensely powerful. (Consider the legend of Britain that Churchill told his beleaguered nation during WW II.)

Another favourite chapter is titled “What could possibly go wrong?” Piper and Samarasekara have soothing news to impart: “All leaders at some point will face a crisis, even if it was not of their making. By recognizing that this is an inherent aspect of leadership, you will be able to avoid personalizing the issue.” (p. 169) “Do not expect others to rally around you when dealing with a crisis.”

Above all, a leader must always remain calm during the storm, setting the tone for everyone else. “This, too, shall pass,” as the saying goes.

Overall, this is a stellar book on women and leadership, written by two who were in the front trenches. Piper and Samarasekara candidly share snippets of their stories—to underscore the points they are making—and these give a warm, relatable dimension to the book. Nerve: Lessons on Leadership is well-organized and manages to engage the reader to think about her own situation (and tailor the advice accordingly). The writing is clear and supportive and very actionable. ♠️