Carbon tax or cap and trade? These are terms bandied about in the political arena as countries decide how to address global warming.

“There is a clear consensus among economists,” said Roger Gordon, professor of economics at University of California at San Diego, “that the best way to address global warming is through the global use of a carbon tax on CO2 emissions.” On January 18, 2024, he was speaking at a webinar as part of the biweekly series of talks, titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics, sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF).

“With a carbon tax,” Gordon said, “prices provide appropriate incentives and then markets generate efficient outcomes.”

The problem, however, is that leaders talk about emission caps, not taxes. Both the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on climate change and the 2015 Paris Climate Accord established “quantity” caps for each country.

The recommended carbon tax rate “equals the present value of the global negative externalities resulting from each extra unit of CO2 emissions.” In economic terms, an externality is an indirect cost to a third party, that is not paid by either the producers or users. [For example, consider the externality of air pollution from motor vehicles: the cost of air pollution to society is not paid by either the manufacturers or drivers, but is a detriment borne by all.]

Gordon referred to work by economist William Nordhaus, who received the Nobel prize “for integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis.” He said Nordhaus gave “a long list of reasons why a carbon tax would have been a better approach.”

Nordhaus observed that quantity caps or “pollution permits” led to “inefficient patterns of abatement” (i.e., reduction of emissions).

“Every year during my career,” Gordon said, “I taught models examining the use of ‘Pigovian’ taxes to correct for generic externalities.” The term “Pigouvian tax” refers to a tax on any market activity that generates negative externalities. The tax is generally set by the government to correct an undesirable or inefficient market outcome.

Carbon tax distortion

“A carbon tax would likely fall heavily on the fossil-fuel industries, reducing the value of their known reserves,” he noted, “so a global carbon tax would have large distributional effects across countries.”

Other questions arise in comparison of carbon tax vs. emissions caps, such as which one is easier to monitor. And which is most likely to be successful in limiting global warming?

Gordon discussed carbon taxes targeting just domestic externalities. As a concrete example, he looked at the case of public transportation. “The government trades off the resource costs of providing [it] with the overall… benefits to households.”

Next, he considered carbon taxes targeting global externalities. “Note the lack of a global income tax to offset resulting distributional effects. The standard presumption is that each country would retain the revenue from its own carbon tax.”

“Many policies lead to higher domestic emissions,” he said, citing a few such as “encouraging use of gas vehicles through providing poor public transport,” and “not providing charging stations for electric vehicles.”

“Such responses undermine the intended abatement.” In other words, the harmful emissions will not be reduced. Distortions to the carbon tax will be many, and it will be “challenging,” he said, to get the heavily emitting countries to participate in the agreement.

“What about the use of quantity caps on emissions?” he asked. When emissions are constrained, the game of constantly adjusting policies disappears.

Another thing about the carbon tax is that the burden does not always fall on the emitters. The emitters pass the costs along to the consumers.

Gordon noted that, as a general rule, the burden of a tax is borne by the most inelastic side of the market. “The demand curve for fossil fuels is very elastic,” once alternative energy sources become available at a comparable price. “In contrast, the supply curve for fossil fuels is very inelastic,” given the large reserves.

Compliance: carbon tax vs. quantity caps

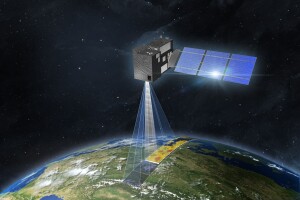

Enforcing the emissions caps would be easier than dealing with carbon tax. “Satellite technology is capable of measuring CO2 emissions from any given area,” he noted. “With quantity caps, detecting excess emissions immediately shows noncompliance.”

However, “with a global carbon tax, it’s unclear whether any detected high emissions are due to offsetting policies—or are simply due to low elasticity.”

He said that “with an inelastic supply of fossil fuels, a carbon tax” will not reduce emissions “until the tax rate is sufficiently high.”

Summary

Gordon’s paper suggests reasons why international agreements have chosen to use quantity caps rather than a carbon tax.

- With a carbon tax, there are many “games” that countries will play to undermine the intended reduction.

- Quantity caps are easier to monitor and enforce.

- Quantity caps provide greater flexibility to achieve broad participation.

- A key concern is to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius. There is no assurance that any given carbon tax rate can come close to this target.

Although there is a “clear consensus” among economists to use a carbon tax to control CO2 emissions, they should seriously consider going to the quantity cap model.

Whether it’s carbon tax or quantity cap, it is crucial to provide an incentive for both industry and consumers to solve the problem of climate change. ♠️