“Income trusts should be viewed as a story in capital markets innovation,” said Jon Northup of Goodmans LLP. He was speaking at a luncheon at the National Club in Toronto, sponsored by the Chartered Financial Analysts (CFA) Society Toronto on March 5, 2013.

The introduction of SIFT (Specified Investment Flow-Through) rules by the Canadian government in October 2006, “effectively eliminated Canadian income trusts,” Northup said. There are two exceptions: (1) a trust that does not involve Canadian real estate, immovable or resource properties used in carrying on a business and (2) a trust that qualifies as a REIT (real estate income trust).

Prior to the 2006 changes, income trusts were treated as flow-through entities for Canadian tax purposes, and were not subject to entity-level taxation. This created a “tax imbalance” and many public corporations began converting their structures to income trusts until the government put a stop to it.

Northup defined a foreign asset income trust (also known as a cross-border trust) as a “tax-efficient vehicle for investment by Canadians in foreign assets, especially oil and gas, and real estate.” It is a “public offering structured with a strong, but not exclusive, emphasis on foreign assets,” he said. Some recent examples are American Hotels REIT and Timbercreek REIT. Milestone REIT is purely States-based. Starlight is very new; it is still in the stage of acquiring a blind pool of assets. “These all trace back to Dundee International.”

Following the 2006 announcement, the demand for income trusts flat-lined. “There just wasn’t the investor appetite,” said Northup. However, there was continued strong demand from Canadian investors for yield-oriented investments. FAITs are generally structured such that Canadians are not subject to foreign taxes or tax filing regulations of the other country.

Why Canada? There are several considerations the sponsor would have for basing the income trust on Canadian soil, said Northup, foremost among these being the sponsor’s own connection to Canada. Typically, the Canadian income trust has a shorter initial public offering (IPO) timeline and a smaller average IPO size. “There’s broad analyst coverage of the small- to mid-cap issuers,” said Northup. In other words, more bang for the promotional buck. He noted there are other reasons, such as higher accepted leverage ratios for real estate issues, and Canada being a generally less litigious society.

The drawback to launching a Canadian income trust is the foreign exchange which, Northup suggested, could be taken care of through judicious hedging.

The issuer of the FAIT is typically a Canadian trust and qualifies as a foreign private issuer under US securities law. Less than 50 percent of trust units can be held by non-Canadians.

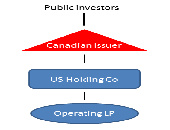

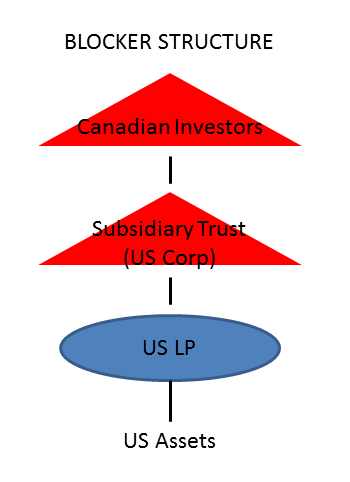

Northup outlined two general tax structures, reproduced in the two diagrams accompanying this posting: “US Blocker,” for example, Eagle Energy Trust, and “US REIT.” The US REIT structure facilitates ownership by others; the US Blocker, less so.

Northup closed with comments on the future opportunities of FAITs. He predicts a slowdown on oil and gas FAITs, and growth in FAITs for operating businesses. As well, they might in future become more global in scope, such as by way of French and German assets, once the European economy starts to turn around. ª

More information on income trusts can be found among the publications at Goodmans LLP at: http://www.goodmans.ca/index.cfm?cm=SiteSearch&ce=Doc&practiceAreaID=0&searchString=income+fund&search