“Active portfolio management is futile,” say some who watch the progression of the financial industry. “Active managers only randomly outperform the stock market as a whole.” Is this true, or have the rumours of its demise been greatly exaggerated?

On June 10, 2021, Philip Young, CFA, welcomed a webinar audience on behalf of the CFA Society of Toronto to consider this very question as they listened to Ronald Kahn, Managing Director, and Global Head of Systematic Equity Research at Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager. He recently co-authored the book Advances in Active Portfolio Management: New Developments in Quantitative Investing.

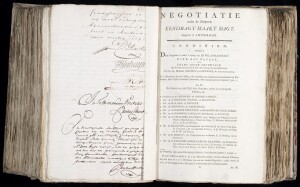

Kahn began with a brief history of investment managers, those specially trained people managing other people’s money, who have been around for centuries. The concept of mutual funds has its modern beginnings in the Dutch financial markets. He showed the opening pages from the Netherlands’ Eendragt Maakt Magt [Unity Makes Strength] investment trust from 1774—the world’s first mutual fund.

Where do the ideas underlying investment management come from? There’s the fundamental analysis that gave rise to the value investing theory of Graham and Dodd. There’s the Modern Portfolio Theory by Harry Markowitz, and, lately, there are counter-developments to active management.

Kahn identified seven trends in investment management. “Many investors are moving from active management to passive.” The active management field is evolving to three branches: indexing (which is not so active); smart-beta methods; and pure alpha.

Investors are asking primarily for two products: purely return-focused; and return- and sustainability-focused.

There are reasons to believe in successful active management. Active managers can identify opportunities for investing, such as areas of excess volatility (Schiller, 1981). Behavioural finance shows there are areas where a savvy investor can exploit mistakes (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). Arbitrage pricing theory (Ross, 1976) can still uncover bargains in some markets. “Informational inefficiencies are narrow and transient sources of return,” he noted, “and as soon as the market understands them, they go away.” So the trick is to stay ahead of the game.

After you take fees into account, “active management is worse than a zero-sum game.” The average active manager tends to underperform, so selecting the best active manager is key.

The fundamental law of active management boils down to the information ratio, IR, the ratio of alpha to risk.

IR = forecasting skill * diversification * efficiency

“Efficiency is a measure of how well you build the portfolio,” he said.

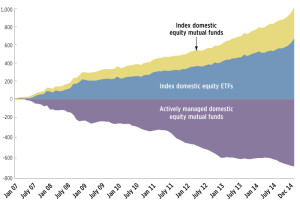

There is increasing competition among active managers for a shrinking dollar. He showed a chart of the growth of actively managed domestic equity mutual funds versus indexed funds.

Kahn described the “academic effect” in which academics investigate and sometimes discover market inefficiencies. “After publication, the inefficiencies don’t work so well.” This effect was reported by McLean and Pontiff in 2016 after studying 75 such events.

Kahn said the market environment is changing due to the growth of high-frequency trading. “The average size of trade has decreased, and average block volume has decreased. “The market has become more fragmented because big investors break up trades so they can’t be followed by block.”

Data trends have undergone a sea-change. In 1985, simply knowing the book-to-price ratio for every S&P 500 stock represented hours of work and was a clear advantage for an investment firm to provide to its clients. But now standard financial data is available to everyone.

“Beyond that, we have seen an explosion in data.” Big data is less structured, larger in volume, higher in frequency, and contains traces of human behaviour and sentiment.

“The explosion of data is the greatest opportunity for active management in many years,” he said. Savvy managers can find out market inefficiencies in advance of others. “And we can find them out in more granular fashion.” As an example, at the start of the pandemic, someone thought to measure the number of cellphones going into Starbucks as an indicator of the company’s financial health.

Another example is how big data can give an indication of consumer confidence in advance of the Michigan survey every month. “Why not use Google search data?” he said. “We can get the data faster, per region, and product-specific.”

Smart beta funds are actively managed products, with some of the benefits of indexed products. “Smart beta is more than a new product. This is a disruptive innovation for active managers.”

“Smart beta factors are already part of investment management.” The four most common factors used are value, momentum, low volatility, and quality. Size also is a frequently used factor (smaller companies tend to be more nimble).

He spoke briefly about sustainable and socially responsible investing. Sometimes a pension plan will specify a list of excluded stocks. Other times the ESG factors must be dug out and compared.

Active management is evolving into two basic activities: smart beta, based on risk premia; and pure alpha, based on informational inefficiencies. Overall, fees have been compressed. “In 2000, active managers charged on average 1.06%. In 2017, they could only charge 0.78%.”

“Investing has become increasingly systematic,” Kahn said. “In future, we will become more specialized.” Nonetheless, active managers can still out-perform the average. ♠️

The chart showing active vs indexed funds as a function of time is from Jesse Felder’s blog.

The cartoon with turkeys and big data is from the website KDnuggets.