The increasing frequency of extreme weather events in Canada has caused the annual payouts for catastrophic insurance claims to skyrocket, according to a recent Statistics Canada report. This is but one small piece of a global picture emerging, where extreme weather events are causing homeowner insurance to increase at a rate higher than inflation. In the worst case, climate change will cause insurance companies to go bankrupt and homeowners will have nowhere to turn.

“Transitions happen shock-wise and are systemic,” said Dirk Schoenmaker, Professor at the Rotterdam School of Management. “What can we do to reduce transition risk?” He was speaking at a webinar on October 17, 2024, presenting results from his article titled Impact of transitions on the financial stability and LOLR roles of central banks. [LOLR = Lender of last resort.] The article is a chapter that will appear in the forthcoming book, Central Bank Capital in Turbulent Times.

His presentation, “Impact of Climate Transition on Financial Stability,” was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics (VSCE).

An article in The Economist in April 2024 quoted a study in Nature that estimates extreme weather events will cause a $25-trillion-dollar hit to homeowners around the world. “Global warming is coming for your home,” he quoted. “Who will pay for the damage?”

“The climate transitions that the Paris Accord requires will be a process of creative destruction,” Schoenmaker said, presenting the X-shaped curve of transition dynamics. The fossil-fuel economy—whose loans are still profitable, he noted—will go through the stages of optimalization, destabilization, disruption, breakdown, and finally phase-out. Meanwhile, the renewables economy will go through the stages of experimentation, acceleration, emergence, institutionalization, and eventually stabilization.

“Transitions can have major implications for the value of a company,” Schoenmaker said. A transition can happen shock-wise at the industry sector level and affect all companies within that sector, a hallmark of systemic risk.

“A company that adapts in a timely manner… can realize its long-term value potential,” he noted. “In contrast, a company that follows a business-as-usual path and fails to adapt can lose its value and go bankrupt.”

In his study, the expected transition loss was calculated as a product of exposure to risk, probability of transition, and loss given transition.

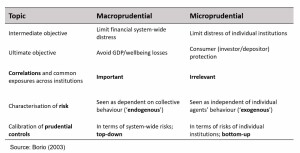

He compared the prudential supervision, or the regulation and supervision of a nation’s financial system, from both the macroprudential (top-down view), and the micro-prudential (bottom-up view) perspectives.

Remember the global financial crisis of 2007-8? “There is a tendency to be active on the micro side (legal instruments), while ignoring the macro side.” Prior to the crisis, the financial system had “Basel internal models with three pillars—state-of-the-art risk management,” Schoenmaker noted, “but nobody was checking housing prices or credit growth.”

He described the main scenario involving climate transition and financial stability. “Severe shocks to companies will happen anyway, either from tightening climate policies (transition risk), physical risk, or legal risk (companied not meeting the Paris obligations).”

He pointed to green swan risks, where “tipping points can make shocks more severe.” Green swan risks are potentially extremely financially disruptive events that could trigger the next systemic financial crisis.

“Let’s reason from the financial stability mandate,” he suggested, “and limit disruptions from climate risks. Take the macro approach and reduce carbon emissions in the economy stepwise.”

What, then, is the most effective carbon reduction pathway? He proposed a “hard macroprudential limit.” In other words, the regulated financial institutions—banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and investment funds—should choose a reduction pathway to get to net zero by 2050.

But which reduction pathway?

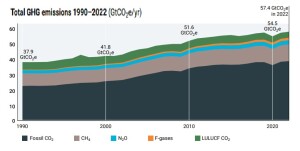

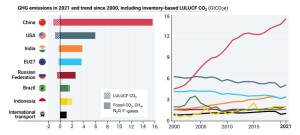

Since signing the Paris Agreement, worldwide emissions have continued to rise with emissions in the EU27 declining only slightly, as the charts show.

“To get to the levels agreed to in Paris, financed emissions will have to come down by 4 percent per year for 25 years,” he noted. The longer we wait to get started, the greater the financial instability due to the transition.

“There is no reason why central banks shouldn’t and couldn’t require better measurement of climate transition immediately!” Schoenmaker suggested banks should foreclose loans to companies with no adaptation plans, “so companies have the incentive to adapt, to keep access to finance.”

His recommendations include:

- Design of the guided transition instrument – 4 percent reduction per year

- Clarification of the legal basis – incorporate in bank transition plans (Credit Institutions Directive, CRD VI)

- Mitigation of global leakages – for all sectors (ESRB, European Systemic Risk Board) and at the global level (Financial Stability Board, FSB)

In conclusion, the best way to limit disruptions to financial stability to promote a smooth transition. Instead of “tinkering with microprudential instruments,” central banks should set a hard macroprudential limit on financed carbon emissions. ♠️

The graphs above are from the VSCE presentation based on the cited article. Permission pending.

The thumbnail image is from earlylearninghq.org.uk. Permission pending.

Schoenmaker, Dirk, Impact of transitions on the financial stability and LOLR roles of central banks (July 29, 2024). Central Bank Capital in Turbulent Times – The Risk Management Dimension of Monetary Policy Instruments, Houben, Broeders and Bonetti (eds), Springer, Forthcoming, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4850317 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4850317

See also “Addressing Climate as a Systemic Risk: A Call to Action for Financial Regulators” by Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance.