Now that the worst of the Covid pandemic appears to be over for North America, inflation has kicked in and investors everywhere are on guard. Is the inflationary trend here for the long term? What, really, lies at the root of this particular instance of inflation? Moreover, what is the best hedge against inflation?

On April 4, 2022, James Montier, a member of the Asset Allocation Committee of the CFA Society of Toronto, gave a one-hour webinar on “Hedging Inflationary Risk.” He is the author of three market-leading books: Behavioral Finance: Insights into Irrational Minds and Markets, Behavioral Investing: A Practitioners Guide to Applying Behavioral Finance, and Value Investing: Tools and Techniques for Intelligent Investment.

“A staggering 77 percent of Americans believe that we are in an inflationary period–more than those who believe in miracles… or aliens,” Montier quipped at the outset of his talk.

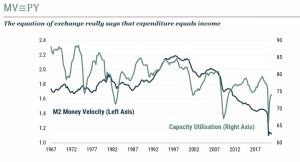

He delved into what causes inflation and he looked at the efforts of economists to model it. “The equation of exchange really says that expenditure equals income,” he noted. The expenditure-output model, or Keynesian cross model, sets expenditure equal to income, and to make it predictive, assumes money velocity is fixed and the output is fixed.

“These are not good assumptions,” Montier said. “Velocity is incredibly unstable, and the output has a cyclical aspect, so there are serious flaws in the money equation.”

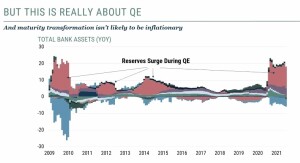

“But this is really about quantitative easing,” he noted, “and maturity transformation isn’t likely to be inflationary.”

He showed a graph where the federal reserves rose to high levels in 2009, 2011, 2014, and 2021. “There is not a direct causal link with inflation.”

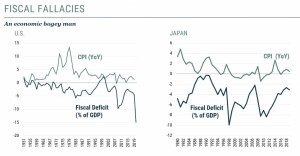

A common explanation for inflation is the size of the fiscal deficit. “But there is no reason to fear fiscal deficits… this has been proven to be an economic bogeyman,” he said. Graphs of the consumer price index (CPI) and the fiscal deficit for both U.S. and Japan showed little or no relationship between CPI and the deficit.

However, a big shock to the economic system might cause tumult. “Hyperinflation is due to supply shocks,” he said, citing the case of Zimbabwe, where the land transfer caused a supply shock when the country did not have enough agricultural output to feed its people and hence it had hyperinflation.

If an aggregate supply shock occurs, this causes a shift in the aggregate supply, and this shifts the aggregate demand, and as it recovers, the price level increases. Thus, he explained, we should expect a level shift in prices, but not a prolonged shift.

The Covid pandemic was a big shock to the global economic system. There was a huge shift in spending patterns at the outbreak of the pandemic. “People bought more goods than usual but there was a collapse in the demand for services,” he said.

He showed inflation as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index (PCE), issued by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

A clash in supply and demand causes an upswing in prices. The relative price of goods and services has been decreasing since the 1950s, but the pandemic caused global supply chain pressure. There was very little demand for oil for a while.

The question becomes: is the upset permanent or transitory? Will inflation be here for the long term? According to Montier’s analysis, “the market and the Fed agree”: they do not think inflation will be here for the long term.

Montier said we must consider the interaction of prices and wages. He quoted an influential post-Keynesian economist, Joan Robinson: “The general level of prices in an industrial economy is determined by the general level of costs, and the main influence upon costs is to be found in the relation between money-wage and the output per unit of employment.”

There is a potential for a wage-price spiral to develop. “To get sustained inflation, you need a wage-price spiral.” There is no sign of a big swing in labour bargaining power. Less than ten percent of the U.S. population belongs to a labour union.

He urged the audience to “look a little deeper behind the numbers.” How else could the labour power in a non-unionized world be measured? In the last 20 or 30 years, he noted that monopolies have grown… but there is more price transparency. There has also been a growth of monopsony, where there is only one purchaser.

The U.S. quit rates of employees had a sudden dive at the outset of the pandemic, but now they are climbing, creating the phenomenon dubbed the Great Resignation. The growth in wages has barely begun. He showed the lowest quartile of wage earners had the bigger jump up, compared to the overall. “The bottom quartile accounts for only 5 to 10 percent of the total income. It won’t created aggregate demand-driven inflation.

“There’s plenty of room for wages to increase,” he said and showed a graph of “firms intending to increase pay” over the next year. It has an upward trend.

After presenting strong arguments for transitory inflation, Montier said, “What if I’m wrong?” He urged the audience to “build robust investment portfolios, not optimal portfolios.”

“Build portfolios that make sense in lots of different outcomes… [One] needs a portfolio that can withstand all kinds of things.”

He advised that investors who are looking for tail-risk insurance should ask themselves, “What risk am I actually trying to hedge?”

“Commodities are actually not a great store of value,” Montier said. “They’ve been losing in aggregate since the 1950s. This comes as a shock to a lot of people.”

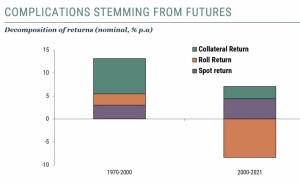

He put up a two-bar graph comparing the source of returns over two time periods. in 1970-2000 the returns normally came from collateral. In 2000-2021 the returns come from roll return. Titled “complications stemming from futures,” the graph shows that “the commodity futures market has now gone contango.” This is considered a normal market, where a buyer is willing to pay more now for a commodity (to be received at some point in the future) than the actual expected price of the commodity at that future point.

Montier recommended against buying gold as a hedge against inflation. “The gold price already reflects fears of inflation…. It’s an expensive insurance—it lacks transparency.”

“Real assets may be the best single store of value,” he concluded.

Although, he noted, “resource-based equities did quite well because they were cheap,” the graph of the value of real estate and equities shows that real assets outperformed equities.” So, he recommended investing in real assets as a hedge against inflation. ♠️

All figures are from James Montier’s talk and are intended as qualitative information at this low level of resolution. Permission is pending.