“The first week is usually a disappointment,” said Catherine Brahic, environment editor at the Economist magazine, “but this [second] week, the attendees are pushing ahead the goals. Now we are in the end game.” On November 11, 2021, the Economist magazine sponsored a webinar featuring two panellists: an editor and a science writer. Before an audience of thousands, each gave a firsthand account of what they had been seeing while they attended the 26th United Nations Climate Change conference, commonly referred to as COP 26, in Glasgow, Scotland.

“The drafts of the papers have come out—they look simple for starters,” Brahic said, but as the drafts circulate, “people add complexity” to address their issues.

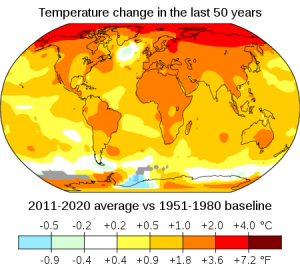

Climate change must be addressed because it is a global operational risk now—and well into the future.

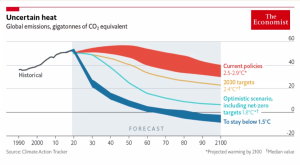

Asked to define success at COP 26, the science writer Oliver Morton said, it “would be a strong new sense of commitment.” He noted that the Paris agreement of 2015 did not mention coal or fossil fuels. “Maybe we can speed up the cycle of NDCs.” Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are climate-related targets for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs).

Of the Glasgow hosts, Morton said, “these guys know how to put on a trade show.” If things don’t work out, it’s traditional to blame the host so there is an incentive to ensure smooth running.

“Until now, the cycle for NDCs is every five years,” said Brahic. “The pledges in 2015 were on track for 2.7 degrees global warming. As of this week, the fresh pledges are now for 2.4 degrees of warming.”

She said it is “still a huge gap for what is needed,” as the CO2 chart shows.

“Strong statements will be seen as a success,” Morton said, “and the language about making commitments is strong.”

Still, as each year goes by, Brahic said, “it will become impossible or at least horrendously expensive, to go back to just 1.5 degrees of global warming by the year 2050.”

“Finance is a huge roadblock–a huge topic,” she said. “Although the text is strong on mitigations, it is weak on the flows of money to the poorer countries. Every country needs to cut emissions, but that is hard to do for countries with emerging economies.”

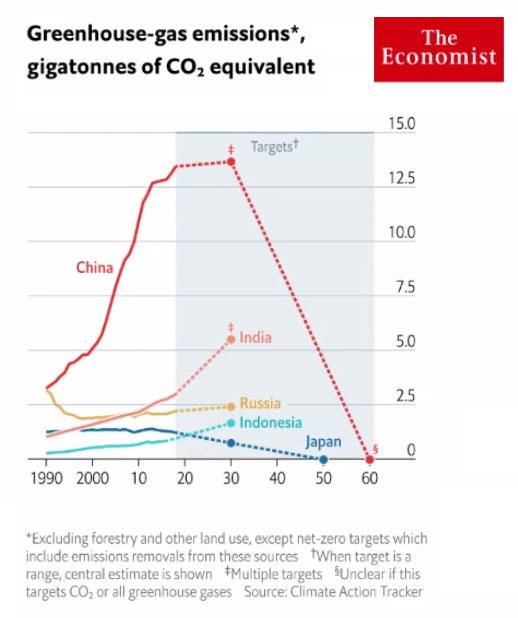

Morton recalled that Indian Prime Minister Modi said in a speech in the first week at COP 26 that his country would need one trillion dollars to make all the changes required to lessen global warming.

“The text of COP 26 is what will be brought to the next round of climate negotiations,” Morton said. “We are asking most of humanity to agree on something. How do you actually have an international process?”

Brahic agreed. “These texts are enhancing the Paris agreement: Paris-plus.” The participants believe if we can have another meeting again in a year—not five years—we can improve on the Glasgow agreement. “This COP shows we’re into different territory.” She said the Paris accord was unique because all countries, rich and poor, were working together. “The Kyoto protocol was only for the Annex 1 countries, the rich world.”

Morton reminded the audience that “at some point, the emissions must go negative.”

“The science is no longer in question,” Brahic said. “Emissions must fall by 45 percent by 2030 to meet the target.”

On November 10, 2021, the U.S. and China made a surprise announcement to COP 26. Brahic said the emissions from China must be drastically curtailed. The graph shows the greenhouse gas emissions for each country. “The goal for GHGs is very unrealistic. You can’t just switch everything off.”

“There is very little detail on methane emissions,” Brahic noted. It was not substantive, just symbolic. “CO2 is the main deal,” she said, and methane is the second biggest. However, methane warms the atmosphere 28 times more than CO2 for the same mass. “Methane … is a very important lever in curbing global temperatures.”

The UN environmental agency UNECE states, “Methane is a powerful greenhouses gas with a 100-year global warming potential 28-34 times that of CO2. Measured over a 20-year period, that ratio grows to 84-86 times. About 60 percent of global methane emissions are due to human activities.”

“No UN text mentions ‘fossil fuels.’ I will be surprised if it stays in the final text,” Brahic said.

“Some companies can see a real advantage to becoming green,” Morton said, but most of them are “just wanting to stay ahead of the regulator.”

Although COP 26 did not achieve all its ambitious goals, Brahic concluded that “the message is slowly getting through to companies: if you want to get ahead of the game, go low-carbon.”♠️

Notes:

Both graphs are from The Economist.

The climate change cartoon is from the news website Powell River Peak. To see footage of recent flooding in British Columbia due to climate change, click here.

All are permission pending.

The map of climate change is from NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio, Key and Title by uploader (Eric Fisk)

The Economist has produced “The Search for Stability,” a 14-page report on climate change.

Click here to read the September posting anticipating COP 26.