When it comes to natural disasters such as flooding, does it make more economic sense to control the flood? Or to sit back, suffer the consequences, and count on insurance?

Climate change leads to more frequent and more intense flooding. As these risks intensify, public funds will often be used to protect communities. Recent work done by economists estimates the amount and distribution of benefits from a major form of public flood risk adaptation, flood control levees. A levee is an embankment built to prevent the overflow of a river.

The efficiency and equity implications of levees were investigated by Joseph Aldy, Professor of Public Policy at Harvard University and Fellow at the think-tank Resources for the Future in Washington, DC. Aldy is also the co-author of the book, Risk Regulation Lessons from Mad Cows. On November 9, 2023, he presented his findings in a webinar as part of the series of talks, the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics, sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF).

Aldy and doctoral student Jacob Bradt studied the impact of levees built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (US ACE), which is the primary federal entity responsible for flood control in the U.S. “Federal levee construction peaked in the 1950s and 1960s,” Aldy said. Each levee requires local cost-share of 45 percent for construction, and afterwards, 100 percent for operation and maintenance. He noted there has been a “recent shift from flood control to policies managing the consequences such as the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).”

“We study levees because it’s unclear if the shift away from flood control to managing the consequences is sustainable,” Aldy said. Levees are similar to other forms of large-scale investments required for public adaptation to climate change, such as sea walls.

Historically, USACE levees have been the single largest federal investment in flood control. “Adaptation to evolving future flood risks requires policies that address vulnerabilities,” he noted, “and policies that manage consequences.”

His project merged data from the USACE National Levee Database with home sale data from the American tech real-estate marketplace company Zillow (1990-2020). The final estimation sample contained 80 levee systems. (Additional data came from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HDMA), the United States Geological Survey National Hydrography Dataset, the FEMA Presidential Disaster Declarations, and NFIP Claims & Policies.)

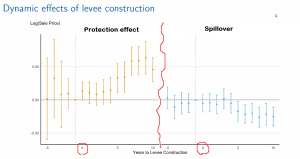

He and Jacob Bradt compared areas that had been protected by the levees from areas that were not protected and thus experienced spillover. [Note: these graphs are shown side by side with a red squiggle separating them]

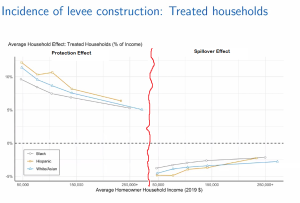

They examined the average transfers of funding by race/ethnicity and income for treated Homeowner Households (HH) and observed a “protection effect” (increased value of property) versus a “spillover effect” (decreased value).

They obtained the main capitalization estimates by taking the difference between specifications with and without levee-year fiscal externalities. They ran several robustness checks.

The research captured three types of benefits and costs:

- Capitalized protection benefits and spillover costs,

- Local public finance externalities (property tax revenue impacts), and

- Upfront construction costs.

In summary, research by Aldy and Bradt found that levee flood protection amounted to 2.8 percent of the home’s value. There were substantial flood risk spillovers, and these reduced the home value by 1.1 percent. Thirty percent of projects impose spillovers on other counties. “Ex post,” he noted, “USACE-constructed levee costs appear to exceed benefits.”

“The USACE levees highlight the difficulties that policymakers face in using existing institutions for climate adaptation,” Aldy said. “The presence of spillover costs and accounting of benefits and costs shows local strategic incentives that determine policy outcomes.”

More broadly, he concluded, economists’ insights can be valuable in studying public investments in climate adaptation. ♠️

Click here to download the research paper this webinar was based on.

Click here to find out about the FRBSF Climate Seminar Series.