What’s been happening in the cryptocurrencies market? Is it all merely speculation or is crypto here to stay? What is the future of broader blockchain technologies? What could regulation mean for the world of decentralized finance (DeFi)?

On February 24, 2022, Helen Joyce, Britain editor of the weekly magazine the Economist, posed questions to her colleagues: Alice Fulwood, Wall Street correspondent at the Economist, and Matthieu Favas, finance editor at the Economist, in order to explore the rise of cryptocurrency and its potential consequences.

“Blockchain can be thought of as a database distributed across many nodes,” Alice Fulwood said, “one that does not depend on centralized entry.”

“Mining for cryptocurrency occurs because it takes time to validate each entry,” said Matthieu Favas, “and so the nodes must compete.” Bitcoin is the actual token the miners receive, if they’ve been mining for it, but there are other cryptocurrencies possible [such as Litecoin, Dogecoin, etc.]. Bitcoin, invented in 2009, is the oldest and most established of the cryptocurrencies.

Ethereum produced one such other cryptocurrency, called Ether, that is considered “nimbler than bitcoin,” said Favas, “because it allows users to do more things.” To date, the total value locked into bitcoin is about $675 billion, and into Ethereum is about $300 billion.

How are non-fungible tokens related to cryptocurrency? asked Helen Joyce, the panel moderator. Both rely on blockchain technology.

Fungibility means the individual units are essentially interchangeable and indistinguishable. “Bitcoin and Ethereum are fungible currencies, like the U.S. dollar,” Fulwood said, “and this is opposite to NFTs, which are tokens that are attached to something, i.e., they are non-fungible.”

“Who likes cryptocurrency?” Joyce asked.

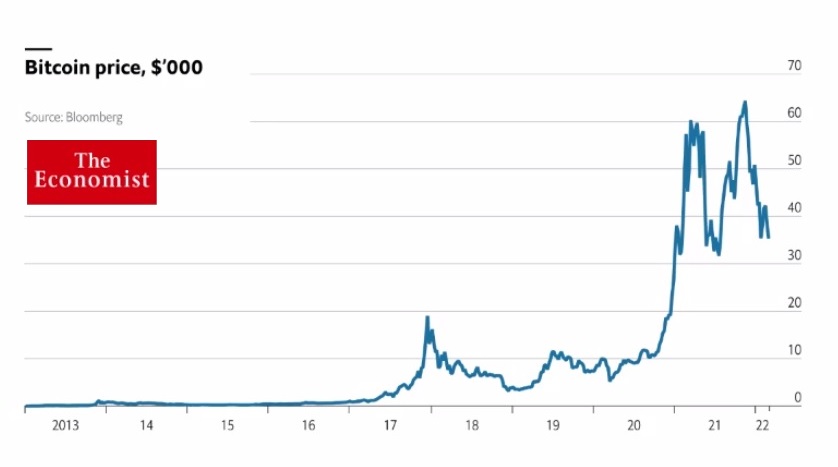

“It’s akin to Marmite,” Fulwood said, because it attracts such passionate enthusiasts and haters. “Some people want to carry out financial transactions distinct from traditional banking.” Also, cryptocurrency is attracting speculators, because it has grown so much in value recently.

“Think of it as a form of digital gold,” said Favas. “It’s meant to resist shock. Although, when markets took fright recently with events in Ukraine, bitcoin value has decreased.”

There is only a maximum number of bitcoins that can be mined, so theoretically the value of each bitcoin will appreciate over time. Favas noted that the buying habits for bitcoin are similar to those for tech stocks. “People buy it when they are excited about the future.” Bitcoin can be a medium of exchange, i.e., act as a true currency, “but that doesn’t happen so much.”

“What’s the catch?” Joyce asked.

“As a currency, it is extremely risky and extremely volatile,” Fulwood said. “On the payment side of things, there is a list of issues to resolve before bitcoin or Ethereum can act as a true currency. For one thing, you have to pay fees to miners who are operating the blockchain technology. You can end up paying hundreds of dollars in fees, which is not convenient if you just want to buy coffee.”

“Is it true that cryptocurrency has a high energy cost?” Joyce asked.

[Ed. Note: A 2021 report in Fortune magazine estimated every bitcoin cost about $100 to produce.]

“Yes, the energy required to do the calculation is due to many people doing the same thing at the same time,” said Favas. “They are all competing on the same problem.” He referred to a recent New York Times study of Bitcoin’s electricity usage compared with that of energy used by entire countries. “It’s a very inefficient way to process.” The only way to lower the carbon footprint is to run the calculations using renewable energy.

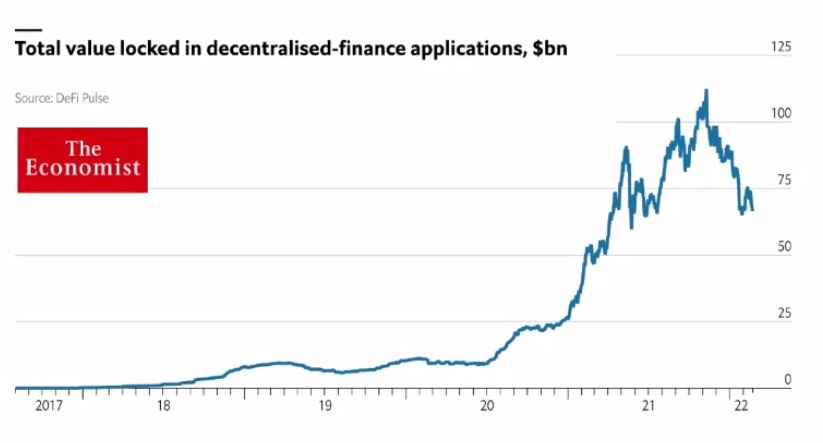

“Is decentralized finance the way to go?” Joyce asked.

“In early 2022, there’s a declining amount of the total value being put into decentralized finance,” Fulwood said. This may be due to the obstacles involved in its use.

She described the exercise carried out by the magazine, so that they could become familiar with the new blockchain technology. For one issue of the Economist, Fulwood and colleagues minted and sold at auction the NFT of the design of the cover (putting the money raised into charity). The cover NFT sold for $420,000 “but we had to pay $500 in fees to get the NFT minted.” The total carbon cost, she said, was on par with “one economy seat on a long-haul flight.”

“What is the geography of crypto?” Joyce asked.

“Mining, trading, gaming, DeFi—these all occur in various places around the world,” Favas said, “but it’s concentrated mainly in the Southern hemisphere.”

“What’s in store for the future of crypto and blockchain? What innovations, what creativity?” Joyce asked.

“No one saw NFTs coming,” said Fulwood. “The interest is to do with single-edition artwork” but there are other applications. For example, “in video games, you can issue special kit with NFT. Companies are trying to build into the Metaverse” that is reportedly coming.

Joyce asked for a comment on interest rate increases and how these will affect centralized and decentralized finance. “Will this encourage interaction between cryptocurrencies and centralized bankers?”

Favas said that he foresaw “new rules and regulations for cryptocurrency. … Regulators are worried about the risks investors are willing to undergo—especially leverage.” Some regulators want to put a cap on leverage—at no more than 20 times the asset value. “We have the anonymized, private, decentralized world versus the regulators.”

The webinar ended with a lively Q & A session touching on a broad range of topics including Russia and China.

To change dollars into bitcoin, Fulwood said, “the off-ramp and on-ramp are heavily regulated to make sure the bitcoin is not being used for illegal purposes.”

“To become mainstream, bitcoin must develop more use-cases. Also, older established institutions must adopt it,” Favas said. Currently, “financial institutions are offering bitcoin products to clients, but they are not investing themselves.” ♠️

The two graphs and three photos are from the Economist subscriber-only webinar. Permission pending.