Climate-related natural disasters are increasing in frequency and severity and costs. Since climate change is not equal across countries, how does a country’s exchange rate respond to such shocks? Furthermore, is it possible to build an economic model to predict future changes?

On April 6, 2023, Galina Hale, professor of economics at the University of California at Santa Cruz, delivered a webinar about the effect of climate change on exchange rates. This was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics. She reported results from a recent paper that she authored for the FRBSF.

“Disasters lead to drops in export production,” Hale said, and going forward, they have negative effects in many ways that affect a country’s currency.

To construct her model, she used the Farhi-Gabaix Rare Disasters model, which is “based on the hypothesis that the possibility of rare but extreme disasters is an important determinant of risk premia in asset markets.” She expanded it “by explicitly modeling belief formation based on data.” (In behavioral economics, people form beliefs about the economic system and act according to mental models of interactions between different economic processes, for example, inflation and unemployment.) She compared what was predicted by her model with the response observed in the data.

What affects FX?

Hale cited the literature on the effects of (climate) disasters. “Everything affects exchange rates.”

- Disasters lead to a drop in exports production;

- Disasters have negative growth effects;

- Disasters can lead to reduction in present value of future revenue stream;

- Disasters lead to welfare reduction through price impact; and

- Physical climate risks affect nominal short-run returns.

She used the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) that covers worldwide extreme events from 1900 to the present. For an event to be called extreme, “at least one of the following criteria must be fulfilled: 10 or more human deaths; 100 or more people injured or left homeless; declaration by the country of a state of emergency; an appeal for international assistance.”

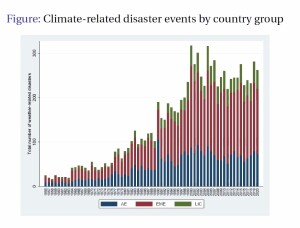

Climate disasters have increased, even beyond what is expected for the increase in population density. As the figure below shows, the number of disasters hovered below 100 until the 1980s, when they rose to about 100 disasters a year. Now there are about 300 climate disasters every year.

The intensity of climate-related disaster events can be categorized by country group (AE = Asia and Europe; EME = emerging countries; LIC = little island countries).

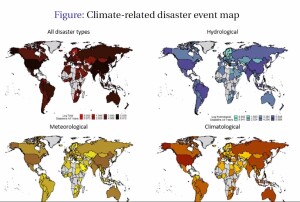

Hale looked at all disaster types, and sub-divided into meteorological disasters, hydrological disasters, and non-climate-based disasters. “This data set provides monthly counts of events by disaster subgroups: geophysical, meteorological, hydrological, climatological, and biological.” Of these, she regarded climate-related disasters as: climatological (including wildfire and drought); meteorological, (including extreme temperatures and storms); and hydrological (floods). Geophysical disasters (volcanos and earthquakes) do not depend on climate and were used for comparison.

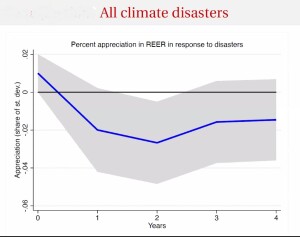

For all climate disasters, in the first four years after an extreme event, the real exchange rate drops, as shown in the graph below. Then it stabilizes at a lower rate than before the disaster.

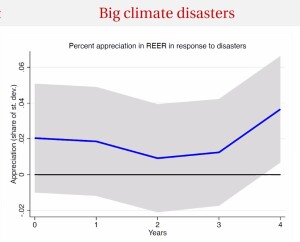

For the biggest climate disasters, there is a net appreciation of the exchange rate.

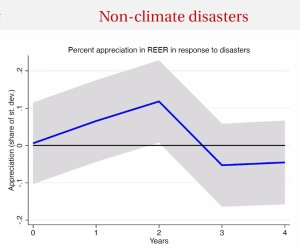

For non-climate disasters, the exchange rate shows a slight appreciation for the first two years, followed by a depreciation.

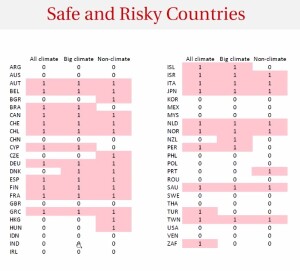

“The response of the real exchange rate to disasters is ambiguous,” she noted. She divided the countries into “resilient” and “risky.” For resilient countries (such as the U.S.), disaster leads to a real appreciation of the exchange rate.

Productivity

Productivity loss is shown below for several countries. The loss is greatest for the economies of Latvia, Lithuania, and Venezuela. Productivity loss is low for countries such as Brazil, Greece, and Thailand.

“The model predicts a real appreciation of safe currencies and real depreciation of risky currencies as a result of disasters,” she noted, “but these effects are modest in magnitude.” This table shows safe vs risky countries, which were obtained through ranking.

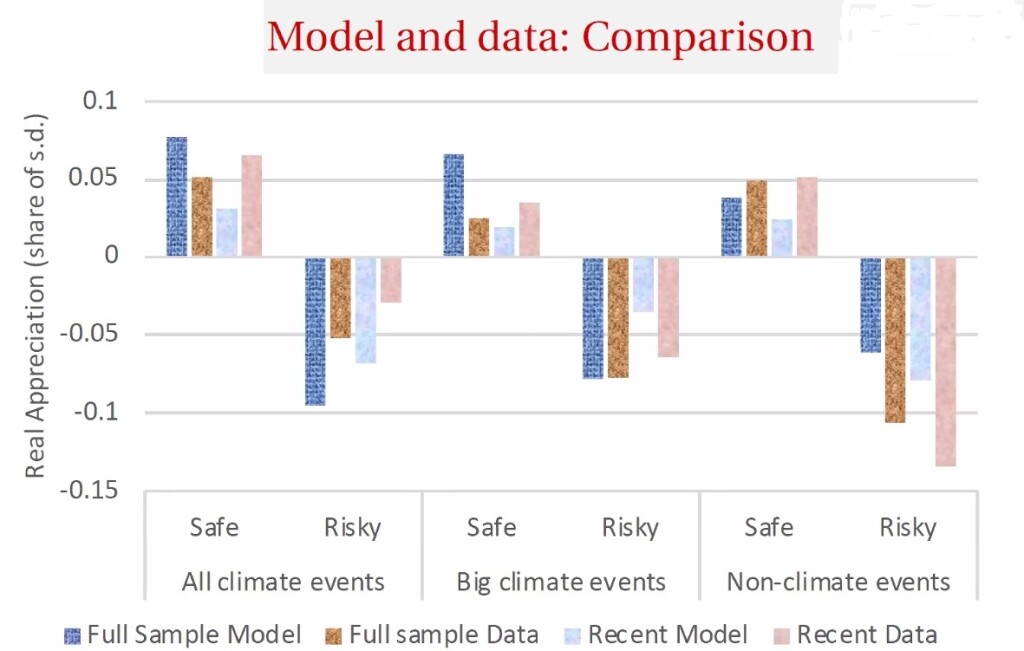

In conclusion, she said that the modified Farhi-Gabaix model was able to predict the “modest effects” of the appreciation of safe currencies and the depreciation of risky currencies as a result of disasters. The results are summarized in the figure below.

For all disaster types, the direction of response in the data was consistent with the model. “For non-climate disasters, we observe an overreaction of real exchange rates relative to the model, while for climate disasters, we observe an underreaction.”

Last, Hale notes that in recent years, “the real exchange rate response to big climate disasters is similar to that of non-climate disasters.”♠️

The graphs are from Galina Hale’s presentation. Permission pending.

Click here to find out about the FRBSF Climate Seminar Series.