It seems not a newscast goes by without mention of carbon taxes, or emissions trading, or severe weather events. As wildfire season ramps up, the benefits to switching to renewable energy are apparent. Gradually—some might say too gradually—climate policy (both to mitigate and adapt to changing conditions) is being implemented. New measures chiefly target industry sectors that have the greatest carbon emissions, such as fossil fuels, agriculture, and fashion.

But how does sustainability affect the cost of capital, in other words, the minimum rate of return a company must earn before generating value?

“There’s plentiful research on the benefits,” said Harrison Hong, Professor of Financial Economics at Columbia University, “but little on the costs to capital of the firms in these sectors.” He was speaking at a webinar on April 18, 2024, on the effects of climate policy. This was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics.

Hong explained that having estimates of the effect on investors’ forecasts of the costs and risks would be useful to guide climate modeling and policy to mitigate climate change. Moreover, companies must consider transition risk as energy sources change.

The machinery for tracking and reporting is still getting put into place. Just this month, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) at the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) tabled a report on financial regulatory concerns about how climate-related risks are reflected in International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) financial statements.

Hong presented results from a recent working paper in which he estimated the response of bond markets to renewable portfolio standards (RPS). The work was a collaboration between him, Jeffrey Kubik at Syracuse University, and Edward Shore at Columbia University.

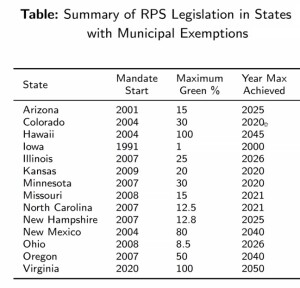

An RPS is a regulation that requires the increased production of energy from renewable energy sources, such as wind, solar, biomass, or geothermal. Fourteen states currently have RPS with municipal exemptions in the U.S.

The RPS guidelines cover power firms in 40 percent of countries that are major emitters. “Wind and solar were 1.5 to 2 times more expensive for the bulk of 2001-2020,” but that may change as economies of scale take over. He said, “Since power firms issue debt to fund investments, we have lots of bond yield data to measure response.”

Do the RPS cause changes in the cost of capital, or it is random fluctuation? To address the issue of causality, Hong and coworkers used certain institutional features of RPS in the U.S. to identify the effects of climate policy.

They estimated the elasticity of credit spread to a given unit of reduction, in this case, to one ton of carbon emissions. Here, credit spread indicates the risk premium for RPS bonds, compared to ordinary bonds (without sustainability criteria).

[Side note to give some idea of “one ton of carbon emissions”: this is the “electricity consumption by 0.65 households in one year in the average Dutch household.” It can be offset by 50 trees growing in one year.]

Hong and collaborators used a structural bond pricing model (Merton-Black-Scholes, 1974) with a modification of stochastic interest rates (introduced by Longstaff and Schwartz, 1995). Abatement costs reduce the cash flow to the firm and the asset value. In the language of the Merton model, abatement costs “lower the distance to default,” meaning they are riskier investments.

They found that “RPS leads to a reduction of carbon emissions of 2.7 million tons per year for the typical producer.” He noted the result was more conservative than two other recent reports (references are in the working paper). Adhering to sustainability standards “comes at a cost of 66 basis points” or 0.66 percent.

“Through the lens of the structural bond-pricing model,” he said, “RPS imposes an annual 1.3 percent tax as a fraction of asset value, which corresponds to investors expecting $50 per ton [to go] to emissions reduction.”

To put abatement costs in perspective, “We perform some simple calculations that link CO2 reduction to power generation,” Hong said. They found that every ton of CO2 generated corresponded to 2.5 megawatt-hours of power.

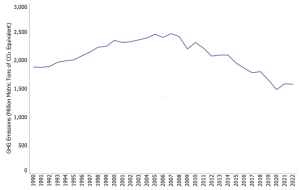

[Side note to give some idea of “one megawatt-hour of power”: this is “1.2 months of electricity for an average American household.” Shown below is a graph from the Environmental Protection Agency of the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by the electrical power industry over the past thirty years.]

“With the price of one kilowatt-hour being $0.11,” Hong noted, “the ratio of revenue from electricity generation to CO2 production is approximately $282.60 per ton of CO2.”

“Firms in the power sector bear more of the tax burden of RPS,” he said, because there is “only a small pass-through of higher renewable costs to consumers.” ♠️

Click here to access the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics.

The GHG from electric power graphic is from the EPA website.