ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing has become a popular choice for many investors. But how reliable are the ratings of the agencies that evaluate stocks for their ESG performance? What kind of discrepancies or “ESG noise” is found among such ratings, and can this be reduced?

On October 5, 2023, Roberto Rigobon, assistant professor at the Sloan School of Management at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), posed these questions during a webinar was part of the series of talks sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF), titled the Virtual Seminar on Climate Economics. His webinar was titled “ESG Confusion and Stock Returns: Tackling the Problem of Noise.”

“Investors want to support ‘green’ funds and punish ‘brown’,” Rigobon said. (Green funds are investments that promote socially and environmentally conscious policies and business practices; brown funds contain investments in fossil fuels.) “Portfolio managers use ESG scores provided by ESG rating agencies. The problem is there is a massive discrepancy between some ESG scores given by rating agencies or data providers.” The discrepancy can be on the order of 50 percent.

Such discrepancies between ratings are what he calls “noise” or “confusion” and it complicates the investor’s choice. Standard regression estimates of the effect of ESG performance on stock returns are therefore biased. He said the noise comes from two sources: “the raw data, which are the answers to questionnaires, and the weights assigned to the data.”

“The ESG rating agencies claim they are measuring the same sources of risk,” so the underlying assumption of his approach is that ESG scores are correlated, even though “they may not be perfectly correlated.”

With no definitive ESG definition, it’s easy to give up on the ESG ratings – or become cynical and try to game them.

Rigobon and fellow researchers used the instrumental value or IV approach, details of which are provided in the research paper “ESG Confusion and Stock Returns: Tackling the Problem of Noise.” Rigobon co-authored this with Florian Berg at MIT Sloan School of Management, Julian F Kölbel at School of Finance at University of St. Gallen, and Anna Pavlova at London Business School and the European-based Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). They wrote, “Specifically, we propose to [determine] a rating of one agency by the ratings of other agencies. Standard regressions then need to be replaced by two-stage least squares (2SLS) regressions.”

The ESG rating agencies of interest are: ISS ESG, MSCI IVA, RepRisk (independent), Refinitiv, SP Global CSA, Sustainalytics, Truvalue Labs (owned by FactSet). They used to include Vigeo-Eiris (now bought by Moody’s).

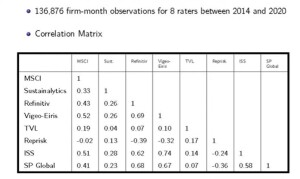

So, what is the agreement, or correlation between the ESG scores of different reporting agencies? This is a figure from the research article (not the webinar):

[Side note. One example of the correlation matrix between the reporting agencies is shown here. Note the high correlation between MSCI and ISS, and the low correction with RepRisk and anything else.]

“There are big differences between raw rankings of firms and noise-corrected rankings,” Rigobon said. Nearly 60 percent of firms moved up or down at least one quintile after correcting for noise.

The researchers found that “standard regression estimates increase on average by a factor of 2.6.” Some agencies’ ESG scores had very large noise-to-signal ratios.

A surprise finding was that they did not find a “greenium,” even though the model predicted this and green stock performed well in the sample period.

“A huge proportion of the ESG questionnaires have missing data,” he said. Imputation, or the process of replacing missing data with substituted values, is a big issue. “For example, those who construct the inflation rate might have to impute missing data,” but they choose an unbiased way to fill the need such as the consumer price index. On the other hand, ESG-related stand-in data is chosen to best reflect sustainability. There are many ways to measure sustainability and he noted that “those who impute their emissions data somehow end up with 17 percent lower emissions.”

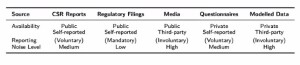

Rating agencies can choose different data sources that qualitatively imply different levels of noise. Mandatory filings tend to have low reporting noise level. Third-party, involuntary ratings tend to have high noise levels.

He discussed the empirical challenges. For example, “returns and ESG performance might be driven by an omitted variable. Hence, ESG scores could also be driven by the same omitted variable.” He said that “pruned instrumental value” worked well for 1-month stock returns.

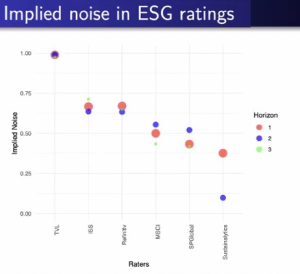

He discussed why alternative noise-reduction procedures were less effective. He said the implied noise in ESG ratings depended on what time horizon was selected.

In conclusion, “we know ESG ratings are noisy.” He noted there are significant discrepancies between the rating agencies, but his proposed method of instrumental valuation provided a way to systematically deal with this. ♠️

Click here to download the research paper this webinar was based on.

The correlation matrix visual is from Roberto Rigobon’s presentation. Permission pending.

The pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey visual is from the MIT Aggregate Confusion Project.

Note there has been a move to create Sustainability Accounting Standards.

Click here to find out about the FRBSF Climate Seminar Series.